Basecamp for Tactical Imaginaries: unbuilds and rebuilds cultural infrastructure to collectively confront the urgencies of today.

Basecamp for Tactical Imaginaries: unbuilds and rebuilds cultural infrastructure to collectively confront the urgencies of today.

Basecamp

Basecamp for Tactical Imaginaries unbuilds and rebuilds cultural infrastructure to collectively confront the urgencies of today.

To meet this moment, in which political, social, economic, and climate crises overlap and amplify each other, requires direct action and intervention. Basecamp radically embodies cultural infrastructure in order to leverage the imagining possible for it. Imagining is central to life in which we convene for resilience, survival, renewal and repair. Basecamp offers itself as site and structure towards intimacy, critique, exploration, possibility, and action.

Read more...

17 May 2025

Rehearsal of Justice: series

Rehearsal of Justice is a series of participatory gatherings in May and June where communities and individuals come together to rehearse and enact justice. Concept, dramaturgy and host Ehsan Fardjadniya.23 May 2025

please register at programma@bakonline.org for zoomlink

Consent Lab Series with Joy Mariama Smith

resheduled: Constent Lab Debrief/reflection online meeting. Friday 13 June 9:00-11:00please register at programma@bakonline.org for zoomlink

3 June 2025

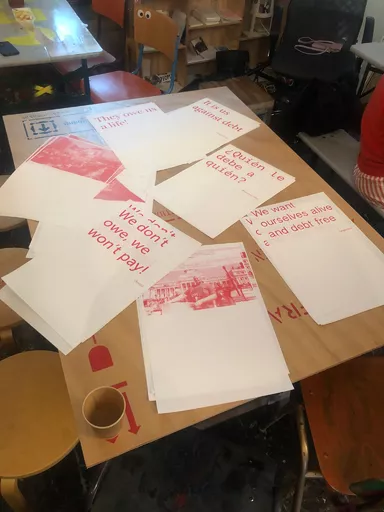

Bring your slogans and any spare cardboard!

Protest art making session

against the Nato Summit.Bring your slogans and any spare cardboard!

8 June 2025

Zapatismo Study Group

Come join us in this collective exploration of other worlds possible, here and there. And to share some warm zapatista coffee with each other12 June 2025

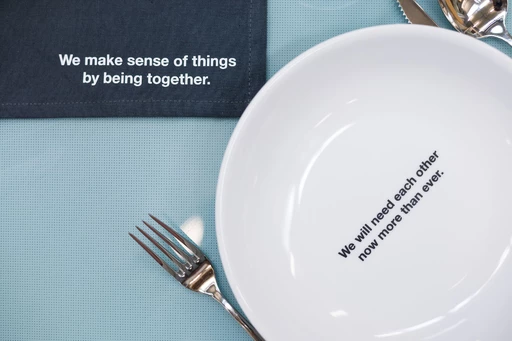

b.ASIC a.CTIVIST k.ITCHEN VOKU

This week we invite our extended network to gather and get to know the whereabouts and vision of Basecamp for Tactical Imaginaries.14 June 2025

Rehearsal of Justice: gathering two and three

Join us for a powerful gathering of legal experts, artists, activists and experience experts.18 June 2025

MAFA Graduation Show: Meanwhile

This exhibition embraces the instability of bodies, histories, and materials in flux.19 June 2025

b.ASIC a.CTIVIST k.ITCHEN VOKU

A space where culture, care, and memory are passed through hands and habits. Knowledge often lives not in books, but in the minor movements of the body: the way we chop, stir, taste. #KitchenTakeover by artists Changli Cui Luo and Mirella Moschella26 June 2025

b.ASIC a.CTIVIST k.ITCHEN VOKU

Open To Public- Donation Based31 March 2025

Welcome to the Basecamp

In this blog I, Angelina Kumar, artist and fellow pioneer for positive change, will attempt, bi-weekly, to capture and share glimpses and insights of the brave and ever evolving journey that is unfolding at the Basecamp for tactical Imaginaries.3 April 2025

All things great and small

This day and meal has given me a refreshing glimpse into potential prospects for the future. Especially, when we work together to make space and place for regenerative ways of being where non-human life is fostered daily.17 April 2025

Glossary of Soup Making

“It is quite a good metaphor and practice to initiate conversations about commoning and in general about politicising food. Because soup is something that everyone relates too since the dawn of time. Some people say that we even come from primordial bro24 April 2025

Memory & Hospicing

This week I was pleasantly surprised to hear that medicine was being explored at the Basecamp. Garage School of Medicine, led by Kari Robertson and Santiago Pinyol. A sweet couple with their 5-year-old daughter.8 May 2025

Reading Counter Power

We need core shared values. Open spaces where we can practice enacting what it means to live in a different kind of world that we envision.29 May 2025

Storytelling: Hi-Story

The stories that are told and shared are the ones that we remember in history, so it’s important to question whose stories are being told and who is telling the story?12 June 2025

Storytelling Workshop (Part 2)

Storytelling is a tool of advocacy. By telling your story in your own words you make people aware of your journey and history.Program

Message from BAK Supervisory Board: Maria Hlavajova bids farewell to BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht

On 30 June 2025, after 25 years of service, BAK’s founding director Maria Hlavajova will step down from her position as general director.

1 April 2025

30 June 2025

Program

BAK announces Basecamp for Tactical Imaginaries: Building Cultural Infrastructure Anew

Marking the beginning of a new phase, BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht embarks upon a six-month period of thinking and planning.

1 January 2025

30 June 2025

Program

The Open Kitchen FreeShop

The FreeShop is a place where nothing is for sale, and everything is free.

1 January 2025

31 December 2025

Program

Climate Propagandas Congregation

A new two-day congregation to study climate propagandas to propagate alternative presents and futures.

14 December 2024

15 December 2024

Program

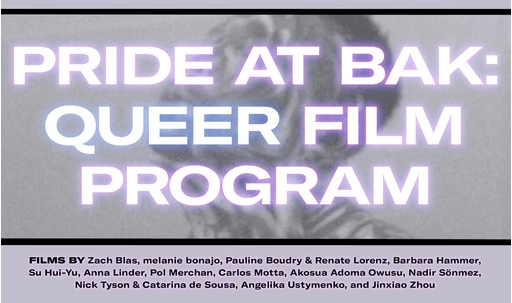

Rhythms/Performances of Subversion & Conformity

A symposium that centers on a table reading of Marival (1996) by Felix de Rooy, a landmark play about Caribbean queer experience in the shadow of Dutch postcolonialism.

1 December 2024

1 December 2024