Author(s)

Stefano Harney & Fred Moten

This is an extract from the chapter “Debt and Study,” in Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (2013). Across its three sections—Debt and Credit, Debt and Forgetting, and Debt and Refuge—this extract traces the sites and practices of “desired” and undesired debt that perforate contemporary financial capitalism and western culture. The text moves through different people who are marked as debt carriers, such as the precariat, the student, and racialized people, among others.

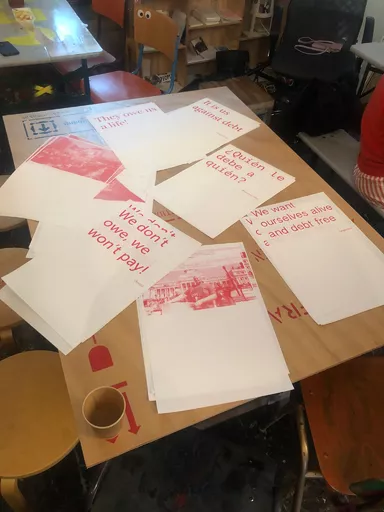

This extract is shared as part of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. It is one of the readings for the Rotterdam reading group Undoing Debt—convened by artists Iliada Charalambous and Philippa Driest—hosted by book and print workshop KIOSK on 28 April 2024. The reading group seeks to collectively unpack debt as a form of gendered and financial violence and see how, in turn, to “undo debt” through learning common political tools and vocabulary inspired by transnational feminist movements.

They say we have too much debt. We need better credit, more credit, less spending. They offer us credit repair, credit counseling, microcredit, personal financial planning. They promise to match credit and debt again, debt and credit. But our debts stay bad. We keep buying another song, another round. It is not credit we seek nor even debt but bad debt which is to say real debt, the debt that cannot be repaid, the debt at a distance, the debt without creditor, the black debt, the queer debt, the criminal debt. Excessive debt, incalculable debt, debt for no reason, debt broken from credit, debt as its own principle.

Credit is a means of privatization and debt a means of socialization. So long as they pair in the monogamous violence of the home, the pension, the government, or the university, debt can only feed credit, debt can only desire credit. And credit can only expand by means of debt. But debt is social and credit is asocial. Debt is mutual. Credit runs only one way. But debt runs in every direction, scatters, escapes, seeks refuge. The debtor seeks refuge among other debtors, acquires debt from them, offers debt to them. The place of refuge is the place to which you can only owe more and more because there is no creditor, no payment possible. This refuge, this place of bad debt, is what we call the fugitive public. Running through the public and the private, the state and the economy, the fugitive public cannot be known by its bad debt but only by bad debtors. To creditors it is just a place where something is wrong, though that something wrong—the invaluable thing, the thing that has no value—is desired. Creditors seek to demolish that place, that project, in order to save the ones who live there from themselves and their lives.

They research it, gather information on it, try to calculate it. They want to save it. They want to break its concentration and put the fragments in the bank. But all of a sudden, the thing credit cannot know, the fugitive thing for which it gets no credit, is inescapable.

Once you start to see bad debt, you start to see it everywhere, hear it everywhere, feel it everywhere. This is the real crisis for credit, its real crisis of accumulation. Now debt begins to accumulate without it. That’s what makes it so bad. We saw it in a step yesterday, some hips, a smile, the way a hand moved. We heard it in a break, a cut, a lilt, the way the words leapt. We felt it in the way someone saves the best stuff just to give it to you and then its gone, given, a debt. They don’t want nothing. You have got to accept it, you have got to accept that. You’re in debt but you can’t give credit because they won’t hold it. Then the phone rings. It’s the creditors. Credit keeps track. Debt forgets. You’re not home, you’re not you, you moved without a forwarding address called refuge.

The student is not home, out of time, out of place, without credit, in bad debt. The student is a bad debtor threatened with credit. The student runs from credit. Credit pursues the student, offering to match credit for debt, until enough debts and enough credits have piled up. But the student has a habit, a bad habit. She studies. She studies but she does not learn. If she learned they could measure her progress, establish her attributes, give her credit. But the student keeps studying, keeps planning to study, keeps running to study, keeps studying a plan, keeps elaborating a debt. The student does not intend to pay.

DEBT AND FORGETTING

Debt cannot be forgiven, it can only be forgotten to be remembered again. To forgive debt is to restore credit. It is restorative justice. Debt can be abandoned for bad debt. It can be forgotten for bad debt, but it cannot be forgiven. Only creditors can forgive, and only debtors, bad debtors, can ofer justice. Creditors forgive debt to offer credit, to offer the very source of the pain of debt, a pain for which there is only one justice, bad debt, forgetting, remembering again, remembering it cannot be paid, cannot be credited, stamped received. There will be a jubilee when the North spends its own money, is left with nothing, and spends again, on credit, on stolen cards, on a friend who knows he will never see that again. There will be a jubilee when the Global South does not get credit for discounted contributions to world civilization and commerce but keeps its debts, changes them only for the debts of others, a swap among those who never intend to pay, who will never be allowed to pay, in a bar in Penang, in Port of Spain, in Bandung, where your credit is no good.

Credit can be restored, restructured, rehabilitated, but debt forgiven is always unjust, always unforgiven. Restored credit is restored justice and restorative justice is always the renewed reign of credit, a reign of terror, a hail of obligations to be met, measured, meted, endured. Justice is only possible where debt never obliges, never demands, never equals credit, payment, payback. Justice is possible only where it is never asked, in the refuge of bad debt, in the fugitive public of strangers not communities, of undercommons not neighborhoods, among those who have been there all along from somewhere. To seek justice through restoration is to return debt to the balance sheet and the balance sheet never balances. It plunges toward risk, volatility, uncertainty, more credit chasing more debt, more debt shackled to credit. To restore is not to conserve, again. There is no refuge in restoration. Conservation is always new. It comes from the place we stopped while we were on the run. It’s made from the people who took us in. It’s the space they say is wrong, the practice they say needs fixing, the homeless aneconomics of visiting.

Fugitive publics do not need to be restored. They need to be conserved, which is to say moved, hidden, restarted with the same joke, the same story, always elsewhere than where the long arm of the creditor seeks them, conserved from restoration, beyond justice, beyond law, in bad country, in bad debt. They are planned when they are least expected, planned when they don’t follow the process, planned when they escape policy, evade governance, forget themselves, remember themselves, have no need of being forgiven. They are not wrong though they are not, finally communities; they are debtors at distance, bad debtors, forgotten but never forgiven. Give credit where credit is due, and render unto bad debtors only debt, only that mutuality that tells you what you can’t do. You can’t pay me back, give me credit, get free of me, and I can’t let you go when you’re gone. If you want to do something, forget this debt, and remember it later.

Debt at a distance is forgotten, and remembered again. Think of autonomism, its debt at a distance to the black radical tradition. In autonomia, in the militancy of post-workerism, there is no outside, refusal takes place inside and makes its break, its flight, its exodus from the inside. There is biopolitical production and there is empire. There is even what Franco “Bifo” Berardi calls soul trouble. In other words there is this debt at a distance to a global politics of blackness emerging out of slavery and colonialism, a black radical politics, a politics of debt without payment, without credit, without limit. This debt was built in a struggle with empire before empire, where power was not with institutions or governments alone, where any owner or colonizer had the violent power of a ubiquitous state. This debt attached to those who through dumb insolence or nocturnal plans ran away without leaving, left without getting out. This debt got shared with anyone whose soul was sought for labor power, whose spirit was borne with a price marking it. And it is still shared, never credited and never abiding credit, a debt you play, a debt you walk, and debt you love. And without credit this debt is infinitely complex. It does not resolve in profit, seize assets, or balance in payment. The black radical tradition is the movement that works through this debt. The black radical tradition is debt work. It works in the bad debt of those in bad debt. It works intimately and at a distance until autonomia, for instance, remembers, and forgets. The black radical tradition is unconsolidated debt.

DEBT AND REFUGE

We went to the public hospital but it was private, but we went through the door marked “private” to the nurses’ coffee room, and it was public. We went to the public university but it was private, but we went to the barber shop on campus and it was public. We went into the hospital, into the university, into the library, into the park. We were offered credit for our debt. We were granted citizenship. We were given the credit of the state, the right to make private any public gone bad. Good citizens can match credit and debt. They get credit for knowing the difference, for knowing their place. Bad debt leads to bad publics, publics unmatched, unconsolidated, unprofitable. We were made honorary citizens. We honored our debt to the nation. We rated the service, scored the cleanliness, paid our fees.

Then we went to the barbershop and they gave us a Christmas breakfast, and we went to the coffee room and got coffee and red pills. We were going to run but we didn’t have to. They ran. They ran across the state and across the economy, like a secret cut, a public outbreak, a fugitive fold. They ran but they didn’t go anywhere. They stayed so we could stay. They saw our bad debt coming a mile off. They showed us this was the public, the real public, the fugitive public, and where to look for it. Look for it here where they say the state doesn’t work. Look for it here where they say there is something wrong with that street. Look for it here where new policies are to be introduced. Look for it here where tougher measures are to be taken, bells are to be tightened, papers are to be served, neighborhoods are to be swept. Anywhere bad debt elaborates itself. Anywhere you can stay, conserve yourself, plan. A few minutes, a few days when you cannot hear them say there is something wrong with you.

Image: Fred Moten and Stefano Harney in conversation as part of Propositions for Non-Fascist Living, October 2017

Related

Held in the context of Usufructuaries of earth: chapter two, reading groups and publication, a reading group was convened by Iliada Charalambous and Philippa Driest on 28 April 2024 titled Undoing Debt, at KIOSK, Rotterdam. The reading group looked at debt as a form of gendered and financial violence and sought how to, in turn, “undo debt” through learning shared political tools and vocabulary inspired by transnational feminist movements.

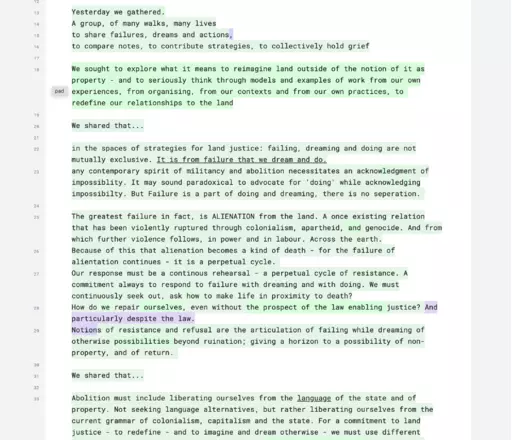

Convened by Johannesburg-based Yvonne Phyllis and MADEYOULOOK (Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho), the working session Failing, Dreaming, Doing: rehearsing abolition sought to conjure alternate imaginaries of life and labor with earth, beyond the regimes of colonial and racial enclosure. The following text was collectively written by the working session’s participants: Brenna Bhandar, Aya Bseiso, Layal Ftouni, Jennifer Irving, Tareq Khalaf, Gelare Khoshgozara, MADEYOULOOK (Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho), Marie Nour Hechaime, Yvonne Phyllis, Philip Rizk, Bobby Sayers, Shela Sheikh, and Kasia Wlaszczyk and was read out by Nare Mokgotho as part of “PROPOSITION 3 Failing, Dreaming, Doing: rehearsing abolition” during the Usufructuaries of earth convention public program, Saturday 25 May 2024 at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht.

________________________________________________________________________________

Held in the context of Usufructuaries of earth: Chapter two, reading groups and publication, a reading group spanning two days was convened by Joud Al-Tamimi and Lama El Khatib on 4 and 5 May 2024 titled And in your throats, a sliver of glass, a cactus thorn and On Value-Disrupting Activity, at bookstore خان الجنوب khan Aljanub, Berlin and Hopscotch Reading Room, Berlin respectively. Mokia Laisin put together a collaborative collage of annotations made during both days of the reading group discussions with input from Miriam Gatt on 4 May 2024.

Held as part of day two of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 25 May 2024, this video documents a closing conversation between Yvonne Phyllis, Denise Ferreira da Silva (online), Verónica Gago, Stefano Harney, Lena Wilderbach, and Brenna Bhandar (online), moderated by Shela Sheikh.

Held as part of day one of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 24 May 2024, this video documents the words of welcome by Maria Hlavajova, followed by a conversation between Marwa Arsanios and Wietske Maas—as means of introduction to the Usufructuaries of earth public program.

Held as part of day one of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 24 May 2024, this video documents a conversation between Brenna Bhandar, Yvonne Phyllis, and Ruth Wilson Gilmore(online), moderated by Layal Ftouni.

Held as part of day one of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 24 May 2024, this video documents a conversation between conversation between Philip Rizk and Marwa Arsanios following a screening of Rizk’s film Mapping Lessons (2020).

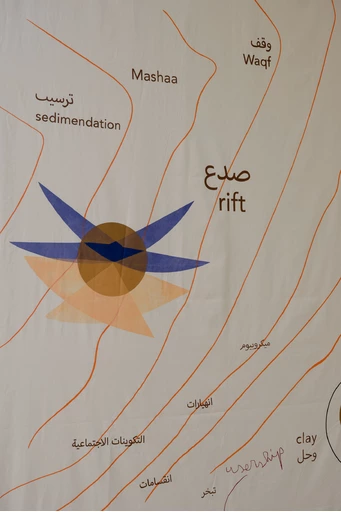

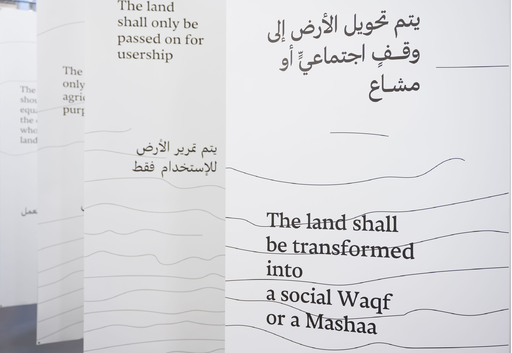

This essay, “Enclosures from Below: The Mushaa’ in Contemporary Palestine,” from geographer and researcher Noura Alkhalili is shared as part of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. It is one of the readings for the Amman reading group convened by artist-led research group Bahaleen involving locally-invited artists and researchers.

This chapter, “Scholar-Activists in the Mix,” from Ruth Wilson Gilmore's Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation (2022) is shared as part of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. It is one of the readings for the Amman reading group convened by artist-led research group Bahaleen involving locally-invited artists and researchers.

This chapter, “Improvement,” from legal scholar Brenna Bhandar’s Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership (2018) is one of the readings for the Amman reading group.

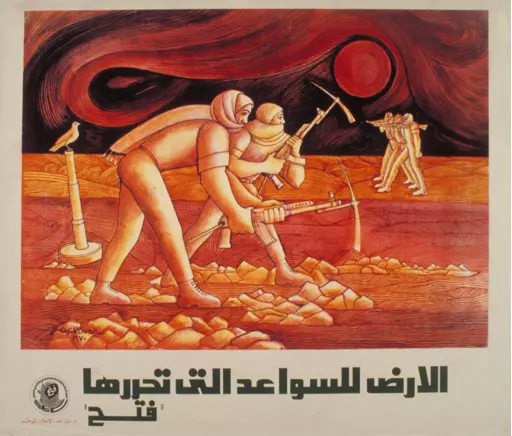

In the context of Usufructuaries of earth: Chapter two, reading groups and publication, a multi-day roaming reading residency, convened by the artist-led research group Bahaleen is held from May 9–13 2024, along the hilltops of Jerash and the edges of Palestine—an hour’s drive from Amman. Invited artists and researchers join Bahaleen in traveling by car and on foot, navigating notions of access and return. Together they grapple with the possibilities of disruption and dissent, aiming to articulate a liberatory vision of the commons from within this geopolitical conjuncture. During the reading residency a board of images and sources were assembled as a harvesting. The images are shared below as screengrabs from this image board, with accompanying links where appropriate.

Originally published in Otherwise Worlds: Against Settler Colonialism and Anti-Blackness (Duke University Press, 2020), this essay, "Reading the Dead: A Black Feminist Poethical Reading of Global Capital" by academic, philosopher, and artist Denise Ferreira da Silva is shared here in the context of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. This chapter is one of the readings for the Berlin reading group convened by Joud Al-Tamimi and Lama El-Khatib, titled “On Value-Disrupting Activity,” at Hopscotch reading room, 5 May 2024. This reading group explores the political and theoretical stakes of value as it links to violences enacted on and through land and property in Palestine and elsewhere.

“What is a revolution that neither overthrows a state order nor institutes a lasting one of its own?” This is the question that teacher, author, and political theorist Nasser Abourahme poses in “Revolution after Revolution: The Commune as Line of Flight in Palestinian Anticolonialism.”

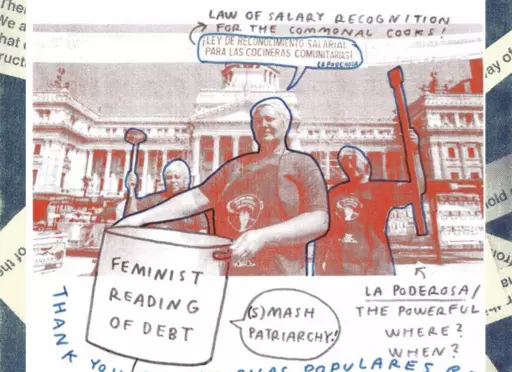

Three excerpts are republished here from researchers and activists Verónica Gago and Lucí Cavallero’s A Feminist Reading of Debt (London: Pluto Press, 2021). The text opens with a simple concept: that contemporary debt cannot be understood by only looking at “public debt,” and must instead look at the indebtedness present in everyday life. The authors call for debt to be adopted by social movements as a key issue, and furthermore, for people to be cognizant of the links between debt and sexist violence.

This is an extract from the chapter “Debt and Study,” in Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (2013). Across its three sections—Debt and Credit, Debt and Forgetting, and Debt and Refuge—this extract traces the sites and practices of “desired” and undesired debt that perforate contemporary financial capitalism and western culture. The text moves through different people who are marked as debt carriers, such as the precariat, the student, and racialized people, among others.

“Riot Now: Square, Street, Commune” is a chapter from political theorist Joshua Clover’s Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprisings (Verso, 2016). Taking the classical Greek agora—a place of assembly and commerce—as a starting point, Clover suggests that it is perhaps no coincidence that many of the riots and occupations that emerged in recent decades either happened or began in modern squares. He speaks of how this emergence of rioters corresponded to “an underlying political-economic unity, a material reorganization of society, which provide[d] them a shared set of problems and a shared arena in which to confront them.”

Charting the interconnectedness of capitalism, colonialism, and nationalism, Peter Linebaugh’s “Palestine & the Commons: Or, Marx & the Musha’a” speaks of “the violence of mapping, titling, buying, and selling which cast people into cities and camps following their expropriation from the land.”

Originally published in Kohl Journal, this interview is between Samanta Arango Orozco, a member of Grupo Semillas, and the artist Marwa Arsanios, who is co-convening with BAK the multi-chaptered project Usufructuaries of earth until 2 June, 2024.

A slow-growing table of contents for the Usufructuaries of earth online reader. The reader emerges, to begin with, as a constellation of archival texts assembled here through the “Usufructuaries of earth” focus on Prospections. Throughout the duration of Usufructuaries of earth project and beyond, diverse content—long reads, interviews, conversations, and visual interventions—will incrementally be (re)published into a public research and learning curriculum that studies histories and propositions of usufruct, of renewing shared practices of usership of and with earth.

“We are in the siege of a nature that has been hurt, divided, defiled, poisoned, harmed, and made to bleed,” writes Pelşîn Tolhildan, member of the Kurdish Women’s Movement.

Usufructuaries of earth is the first comprehensive exhibition of Marwa Arsanios’s work in the Netherlands. The exhibition foregrounds the artist’s collaborative approach to bringing together ecological, feminist, and decolonial knowledges and practices that put forward ideologies of usufruct, unhinging property-relations from the idiom of individuated possession and toward forms of common, more-than-human userships. Here is an audio tour of the exhibition given by BAK convenor of research and publications Wietske Maas.