Author(s)

Ruth Wilson Gilmore

This chapter, “Scholar-Activists in the Mix,” from Ruth Wilson Gilmore's Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation (2022) is shared as part of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. It is one of the readings for the Amman reading group convened by artist-led research group Bahaleen involving locally-invited artists and researchers.

When I set out in 1993 to earn a PhD, a bookseller acquaintance praised my choice of field, saying “Geography is the last materialist discipline.” Colleagues across the political spectrum generally bristle at his assertion, while I have cherished it as one of two mantras I use when the going gets tough. The second, dating from the same week in 1993, is an exchange I had with a former student who was completely perplexed by my decision. When she asked why an activist lecturer on race, culture, and power would go study “Where is Nebraska?” I replied that actually I was going to study “Why is Nebraska?” This explanation was such a hit among geographers that it turned up, without attribution, in the Lingua Franca guide to graduate school.

Motivated to learn how to interpret the world in order to change it,See Karl Marx, “Theses on Feuerbach,” in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Selected Works, vol. 1 (1845; repr. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969), p. 15. I found in Geography ways to contemplate and document the vibrant dialectics of objective and subjective conditions that, if properly paid attention to, help reveal both opportunities for and impediments to human liberation. Space always matters, and what we make of it in thought and practice determines, and is determined by, how we mix our creativity with the external world to change it and ourselves in the process.See Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1 (1867; repr. New York: Penguin, 1976), p. 283. In other words, one need not be a nationalist, nor imagine self-determination to be fixed in modern definitions of states and sovereignty, to conclude that, at the end of the day, freedom is a place.

How do we find the place of freedom? More precisely, how do we make such a place over and over again? What are its limits, and why do they matter? What, in short, is the mix? In this brief essay I wish to outline how the lively hyphen that articulates “scholar” and “activist” may be understood, and enacted, as a singular identity. These pages are not prescriptive but rather suggestive. If they serve to raise Geography’s profile in public debate, that will be great, because my interest is in proliferating, rather than concentrating, ways of thinking. The debates that most concern me center on how organizations and institutions craft policies that result in building social movement (through nonreformist reforms) rather than in areal redistribution of harms and benefits.

The projects from which I have derived these lessons all involve novel practices of place-making that revise understandings and produce new senses of purpose. For example, in the effort to dismantle the prison-industrial complex, one trajectory frames prisons as new forms of environmental racism which are equally, if differently, destructive of the places prisoners come from and the places where prisons are built.“The Other California” (with Craig Gilmore), in Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation (London: Verso, 2022), pp. 242–258. Such destruction shortens lives, and all people caught in prison’s gravitational field are vulnerable to its ambient material and cultural toxicities. Through forging links across enormous social and geometric distances, this activism extends the potential array of campaigns that abandoned rural and urban communities may design in their demand for both living and social wages. What rises to the surface is how people who are skeptical of “the government” begin to engage in what I call “grassroots planning”—a future orientation driven by the present certainty of shortened lives.

Moving to another example, which approaches the problem of “planning” for those specifically excluded by state practices, organizations in urban and rural California are beginning to examine, through community design workshops, forums, and other means, the continuum (rather than the difference) between undocumented workers and documented felons. Both groups are equally unauthorized to make a living and participate fully in the institutions of everyday life.See Victor Hugo, Les Misérables (1862; repr. New York: New American Library, 1987). All these projects have the potential for fostering previously unimagined or provisionally forgotten alignments,See Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra. and they are connected by the likelihood that the folks who are becoming activists or reviving activism will die prematurely of preventable causes.See Michael Greenberg and Dona Schneider, “Violence in American Cities: Young Black Males Is the Answer, but What Was the Question?” Social Science and Medicine 39 (1994), pp. 179–187; “Race and Globalization,” in Gilmore, Abolition Geography, pp. 107–131.

Engaged scholarship and accountable activism share the central goal of constituting audiences both within and as an effect of work based in observation, discovery, analysis, and presentation. Persuasion is crucial at every step. Neither engagement nor accountability has meaning, in the first instance, without potentially expanded acknowledgment that a project has the capacity to flourish in the mix. As a result, and to get results, scholar-activism always begins with the politics of recognition. Whether a project is compensatory, interventionist, or oppositional, the primary organizing necessary to take it from concept to accomplishment (and tool) is constrained by recognition. Recognition, in turn, is the practice of identification, fluidly laden with the differences and continuities of characteristics, interests, and purpose through which we contingently produce our individual and collective selves.Stuart Hall, “Cultural Identity and Diaspora,” in Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman, eds., Colonial Discourse/Post-colonial Theory (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), pp. 392–403; “‘You Have Dislodged a Boulder,’” in Gilmore, Abolition Geography, pp. 355–409. Such cultural (or ideological) work connects with, reflects, and shapes the material (or political-economic) relations enlivening a locality as a place that necessarily links and represents other places at a variety of time-space resolutions.Doreen Massey, Space, Place and Gender (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994).

Consistently, then, the scholar-activist works in the context of ineluctable dynamics that force her—deliberately yet inconsistently—at times to confirm and at times to confront barriers, boundaries, and scales.Gilmore, “‘You Have Dislodged a Boulder’”; Cindi Katz, “On the Grounds of Globalization: A Topography for Feminist Political Engagement,” Signs 26 (2001), pp. 1213–1234; Cindi Katz, “Vagabond Capitalism and the Necessity of Social Reproduction,” Antipode 33 (2001), pp. 709–728. This is treacherous territory for all of us who wish to rewrite the world. There is plenty of bad research produced for all kinds of reasons (engaged or not) and lousy activism undertaken with the best intentions. In the following pages I will highlight what I have found to be key conceptual problems and perils, and end by suggesting some promising pathways that might be introduced into the mix.

Problems

Three kinds of problems dog the diligent scholar-activist in her desire to make the hyphen make a difference. Theoretical, ethical, and methodical challenges grip a project from its earliest moments of conception. Let us take them in turn.

Theoretical

Theory is a guide to action; it explains how things work. What can and should be made of this? The way “good theory in theory”Toni Negri, “Marx on Cycle and Crisis,” Revolution Retrieved (London: Red Notes, 1968), p. 47. stands up to the test of practice partly depends on how the researcher understands quantum physics’ key insight that the observer and the observed are in the same critical field.Karen Barad, “Getting Real: Technoscientific Practices and the Materialization of Reality,” Differences 10 (1998), pp. 87–128. As may be said of all human activity that produces change, scholar-activism is caught in a social-spatial opening—sometimes a full-blown crisis, sometimes only a conjuncture or brief moment of instability—where historical becoming, or subjectivity,See Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks (New York: International Publishers, 1971). meets up with historical constraint, or objectivity.Immanuel Wallerstein, Unthinking Social Science: The Limits of Nineteenth-Century Paradigms (Cambridge: Polity, 1991). The external world is real, we are of it no matter what we decide to do, its mutability and our own are not without limit, and yet what we decide to do makes it, and us, different. Here, the theoretical does not collapse into an endless contemplation of the researcher and her feelings or insecurities or the compromises and complications inherent in her “location.”The superb example of a book that successfully negotiates pitfalls while embracing complexity is Leela Fernandes, Producing Workers: The Politics of Gender, Class, and Culture in the Calcutta Jute Mills (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997). All of those things matter but, if the object of study is never a thing but rather relations, then the way theory moves to action always exceeds, while being linked to, the researcher’s individual mediation. Theory is, in this sense, a method.

Ethical

As a result of heinous practices carried out at the expense of people’s lives and well-being, researchers rightly hesitate before connecting “human” and “experiment,” and US universities have developed complicated apparatuses to safeguard human subjects from inhumane protocols. In addition to the scandal of harmful inquiry, there is another aspect of ethics for scholar-activists to think through in considering the normative dimensions of projects intended for the mix. What scholar-activism does is forthrightly bring the experimentation of academic research into relation with the experimentation of (any) political action. In both, whether predictions turn out to be strong or weak, effects and outcomes matter and provide the basis for a new plan (or theory) to move forward.

Methodical

Theoretical and ethical considerations embed the third problem. If methodology is how research should proceed, the methodical, short of “ology’s” comprehensive brief, more narrowly focuses on the plodding problem of questions. What kinds of questions should scholar-activists ask? Every question is an abstraction made of concentrated curiosity. Curiosity itself is not free-floating, but rather shaped by the very processes through which we make places, things, and selves. Thus, no matter how concrete, a question’s necessary abstraction is also always a distortion—as cartographers, artists, and quantum physicists will readily attest. But all this means opportunity, rather than hopeless gloom, when questions have stretch, resonance, and resilience.

Stretch

Stretch enables a question to reach further than the immediate object, without bypassing its particularity—the difference, for example, between asking a community “Why do you want this development project?” and asking “What do you want?”

Resonance

This enables a question to support and model nonhierarchical collective action through producing a hum that, by inviting strong attention, elicits responses that do not necessarily adhere to already-existing architectures of sense-making. Ornette Coleman’s harmolodics exemplify how such a process makes participant and audience a single, but neither static nor closed, category.Jennifer Rycenga, “The Composer as a Religious Person in the Context of Pluralism,” PhD dissertation, Graduate Theological Union (1992), pp. 261–289.

Resilience

Resilience enables a question to be flexible rather than brittle, such that changing circumstances and surprising discoveries keep a project connected with its purpose rather than defeated by the unexpected. For example, the alleged relationship between contemporary prison expansion and slavery crumbles when the question poses slavery-as-uncompensated labor, because very few of the USA’s 2.2 million prisoners work for anybody while locked in cages. But the relationship remains provocatively stable when the question foregrounds slavery as social death and asks how and to what end a category of dehumanized humans is made from peculiar combinations of dishonor, alienation, and violent domination.Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982); Golden Gulag.

Clearly, all three problems are related, and the mode I have presented them in here is an attempt to make what is strange familiar, and what is familiar strange. We will return to that issue, in a brief discussion of categories, further on. First, let us pause and consider the substantial perils invoked by the discussion so far.

Perils

The perils inherent in searching for the liveliness in the scholar-activist’s hyphen fall into two general tendencies: technocracy and disabling modesty.

Technocracy

Mixing social-science expertise into experimentation in the nonacademic world can reinforce the bad idea—promoted and affirmed in an innumerate culture where statistics are magic (with the hit-or-miss properties of all magical forces)—that better information from better data is what is needed to make the world better.Robert W. Lake, “Structural Constraints and Pluralist Contradictions in Hazardous Waste Regulation,” Environment and Planning A 24 (1992), pp. 663–681. This way of thinking leads to the supremacy of intrastructural policy tweaking and perpetual displacement machines, and reduces the possibilities of complexly thoughtful action to, for example, expanding reliance on narrowly focused nongovernmental organizationsJennifer Wolch, The Shadow State: Government and the Voluntary Sector in Transition (New York: The Foundation Center, 1989); Andrea Smith, “Bible, Gender and Nationalism in American Indian and Christian Right Activism,” PhD dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz (2002); see also Smith’s Native Americans and the Christian Right: The Gendered Politics of Unlikely Alliances (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008). that are locked into endless rehearsals of injury and remedy.“Terror Austerity Race Gender Excess Theater,” in Gilmore, Abolition Geography, pp. 154–175; Gilmore, “‘You Have Dislodged a Boulder,’” in Gilmore, Abolition Geography, 355–409; Wendy Brown, States of Injury (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994).

Disabling Modesty

If, on the one hand, nonacademic activists expect too little from the social scientist’s toolkit, on the other hand, the reluctance of engaged scholars to raise challenges in the mix can make the hyphen inactive insofar as the scholar becomes irrelevant. Here of course is where the question of questions comes most vividly into view. In the constant rounds of discussion and reflection through which engaged work proceeds, the strictly attentive practice of making the familiar strange is as important in extramural circles where projects come into being as it is in the halls of academia where scholar-activists struggle to legitimate our trade.

Careful focus on the interworkings of the theoretical, ethical, and methodical as outlined above at least partially averts these tendencies. The next section touches on what such focus might consist of.

Promising Pathways

One of the key tensions in any kind of experiment (research, activism) centers on the collision between creativity on the one hand and already-existing frameworks and categories on the other. Categories are not only useful but also seem fundamentally to organize human thinking.George Lakoff, Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996). There is a difference, however, between the general fact (if we wish to accept its accuracy) that human thought is categorical and the practice that plagues much research and activism whereby particular social and spatial categories get reified by studying or acting on them as ahistorical durables.For exemplary critiques, see the following: on paradigm shifts, see Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962); on race and categories, see Denise Ferreira da Silva, Race and Nation in the Mapping of Modern Global Space (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005); on radical traditions, see Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism and the Making of the Black Radical Tradition (London: Zed Books, 1982); on theory, see Barbara Christian, “The Race for Theory,” Cultural Critique 6 (1987), pp. 51–63; and on topography, see Cindi Katz, “On the Grounds of Globalization: A Topography for Feminist Political Engagement,” Signs 26 (2001), pp. 1213–1234. So too with frameworks: the challenge is not to be more logical, or more reasonable, but rather more persuasively based in the real material of the everyday, which means performing with the kind of attention Coleman’s harmolodics requires to produce beautifully unexpected sound.

Two of the pathways are rather self-explanatory, and I will only name and briefly describe them, saving my scarce remaining space for the third.

Research Design and Analysis

By now it goes without saying that purpose leads, and the way a project’s design and analysis proceed depends a lot on what work the outcome is supposed to do. If it is supposed to bring a different solution to a crisis than the remedies current power-blocs propose, then what will it take to mobilize communities to demand certain kinds of decisions? Where might they go wrong? Who will know, and how?

Scale and Rhetoric

Persuasion requires barriers to fall, at least momentarily. Scale suggests the actual and imaginative boundaries in which political geographies are made and undone.Neil Smith, “Contours of Spatialized Politics: Homeless Vehicles and the Production of Geographical Scale,” Social Text 33 (1993), pp. 55–81. A scholar-activist’s project both defines and produces an opening on the ground, through which creative possibility can move.See, for example, Laura Pulido, “Rethinking Environmental Racism: White Privilege and Urban Development in Southern California,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90 (2000), pp. 12–40.

Credibility and Afetishism

In order for the scholar-activist to maintain the vitality of the hyphen, she has to toe a line that keeps moving. Her credibility is a function of many relationships—with other academics, with sources, with organizations. Every graduate student learns, at about the time of oral exams, to say, at long last, “I don’t know.” The important demystification of scholarship makes its work, in my view, stronger. This strength derives from constantly reflecting on the theoretical, the ethical, and the methodical while always acting. Yet the way through the twinned jaws of technocracy and disabling modesty is also marked, provisionally, by care around three troubling categories that can trip us along the route: object, truth, and authenticity. Objectivity cannot ever be passive,Barad, “Getting Real.” truth cannot ever be comprehensive (which means pessimism of the intellect has to be balanced by optimism of the will),Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks. and authenticity is a projection of shadow and light that shifts in time and place. Indeed, object, truth, and authenticity return us to an original argument of these remarks, which is how recognition permeates what we do, and how, and why. Recognition and redistribution are, then, two sides of the same coin.

Conclusion

Geography is an interdisciplinary discipline, and its relative irrelevance and “pariah”Wallerstein, Unthinking Social Science. status in the twentieth century ironically enhances its current promise because it is so wide open for good use. Certainly, the key words of the contemporary moment—globalization, racism, migration, war, new imperialism, environmental degradation, fundamentalism, human rights—bespeak and connect (what, in sum, “articulation” is) all kinds of complexities.

In my view, interdisciplinarity and coalition-building are, like recognition and redistribution, two sides of a singular capacity. What the outcome could be, with scholar-activists in the mix, is the harmolodics of novel scales—which we might call a renovated “third world” or Bandung-consciousness—and subsequent differential alignments for the twenty-first century.

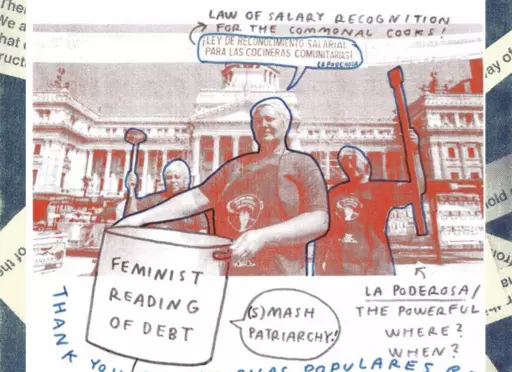

Related

Held in the context of Usufructuaries of earth: chapter two, reading groups and publication, a reading group was convened by Iliada Charalambous and Philippa Driest on 28 April 2024 titled Undoing Debt, at KIOSK, Rotterdam. The reading group looked at debt as a form of gendered and financial violence and sought how to, in turn, “undo debt” through learning shared political tools and vocabulary inspired by transnational feminist movements.

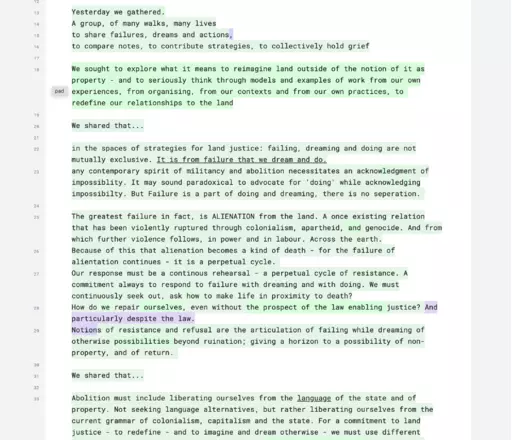

Convened by Johannesburg-based Yvonne Phyllis and MADEYOULOOK (Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho), the working session Failing, Dreaming, Doing: rehearsing abolition sought to conjure alternate imaginaries of life and labor with earth, beyond the regimes of colonial and racial enclosure. The following text was collectively written by the working session’s participants: Brenna Bhandar, Aya Bseiso, Layal Ftouni, Jennifer Irving, Tareq Khalaf, Gelare Khoshgozara, MADEYOULOOK (Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho), Marie Nour Hechaime, Yvonne Phyllis, Philip Rizk, Bobby Sayers, Shela Sheikh, and Kasia Wlaszczyk and was read out by Nare Mokgotho as part of “PROPOSITION 3 Failing, Dreaming, Doing: rehearsing abolition” during the Usufructuaries of earth convention public program, Saturday 25 May 2024 at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht.

________________________________________________________________________________

Held in the context of Usufructuaries of earth: Chapter two, reading groups and publication, a reading group spanning two days was convened by Joud Al-Tamimi and Lama El Khatib on 4 and 5 May 2024 titled And in your throats, a sliver of glass, a cactus thorn and On Value-Disrupting Activity, at bookstore خان الجنوب khan Aljanub, Berlin and Hopscotch Reading Room, Berlin respectively. Mokia Laisin put together a collaborative collage of annotations made during both days of the reading group discussions with input from Miriam Gatt on 4 May 2024.

Held as part of day two of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 25 May 2024, this video documents a closing conversation between Yvonne Phyllis, Denise Ferreira da Silva (online), Verónica Gago, Stefano Harney, Lena Wilderbach, and Brenna Bhandar (online), moderated by Shela Sheikh.

Held as part of day one of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 24 May 2024, this video documents the words of welcome by Maria Hlavajova, followed by a conversation between Marwa Arsanios and Wietske Maas—as means of introduction to the Usufructuaries of earth public program.

Held as part of day one of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 24 May 2024, this video documents a conversation between Brenna Bhandar, Yvonne Phyllis, and Ruth Wilson Gilmore(online), moderated by Layal Ftouni.

Held as part of day one of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 24 May 2024, this video documents a conversation between conversation between Philip Rizk and Marwa Arsanios following a screening of Rizk’s film Mapping Lessons (2020).

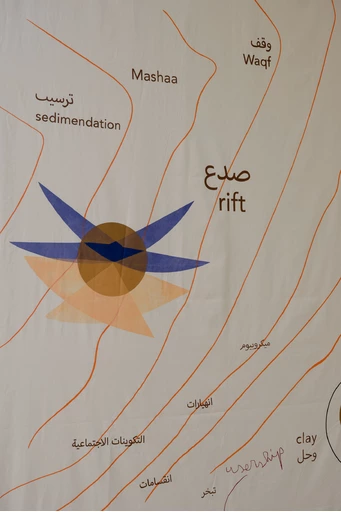

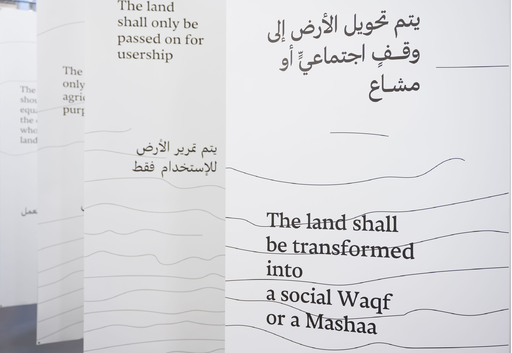

This essay, “Enclosures from Below: The Mushaa’ in Contemporary Palestine,” from geographer and researcher Noura Alkhalili is shared as part of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. It is one of the readings for the Amman reading group convened by artist-led research group Bahaleen involving locally-invited artists and researchers.

This chapter, “Scholar-Activists in the Mix,” from Ruth Wilson Gilmore's Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation (2022) is shared as part of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. It is one of the readings for the Amman reading group convened by artist-led research group Bahaleen involving locally-invited artists and researchers.

This chapter, “Improvement,” from legal scholar Brenna Bhandar’s Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership (2018) is one of the readings for the Amman reading group.

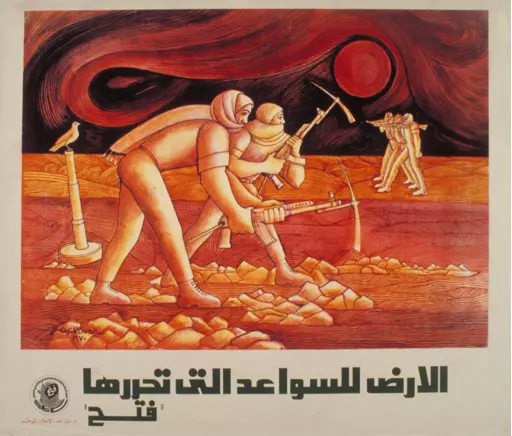

In the context of Usufructuaries of earth: Chapter two, reading groups and publication, a multi-day roaming reading residency, convened by the artist-led research group Bahaleen is held from May 9–13 2024, along the hilltops of Jerash and the edges of Palestine—an hour’s drive from Amman. Invited artists and researchers join Bahaleen in traveling by car and on foot, navigating notions of access and return. Together they grapple with the possibilities of disruption and dissent, aiming to articulate a liberatory vision of the commons from within this geopolitical conjuncture. During the reading residency a board of images and sources were assembled as a harvesting. The images are shared below as screengrabs from this image board, with accompanying links where appropriate.

Originally published in Otherwise Worlds: Against Settler Colonialism and Anti-Blackness (Duke University Press, 2020), this essay, "Reading the Dead: A Black Feminist Poethical Reading of Global Capital" by academic, philosopher, and artist Denise Ferreira da Silva is shared here in the context of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. This chapter is one of the readings for the Berlin reading group convened by Joud Al-Tamimi and Lama El-Khatib, titled “On Value-Disrupting Activity,” at Hopscotch reading room, 5 May 2024. This reading group explores the political and theoretical stakes of value as it links to violences enacted on and through land and property in Palestine and elsewhere.

“What is a revolution that neither overthrows a state order nor institutes a lasting one of its own?” This is the question that teacher, author, and political theorist Nasser Abourahme poses in “Revolution after Revolution: The Commune as Line of Flight in Palestinian Anticolonialism.”

Three excerpts are republished here from researchers and activists Verónica Gago and Lucí Cavallero’s A Feminist Reading of Debt (London: Pluto Press, 2021). The text opens with a simple concept: that contemporary debt cannot be understood by only looking at “public debt,” and must instead look at the indebtedness present in everyday life. The authors call for debt to be adopted by social movements as a key issue, and furthermore, for people to be cognizant of the links between debt and sexist violence.

This is an extract from the chapter “Debt and Study,” in Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (2013). Across its three sections—Debt and Credit, Debt and Forgetting, and Debt and Refuge—this extract traces the sites and practices of “desired” and undesired debt that perforate contemporary financial capitalism and western culture. The text moves through different people who are marked as debt carriers, such as the precariat, the student, and racialized people, among others.

“Riot Now: Square, Street, Commune” is a chapter from political theorist Joshua Clover’s Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprisings (Verso, 2016). Taking the classical Greek agora—a place of assembly and commerce—as a starting point, Clover suggests that it is perhaps no coincidence that many of the riots and occupations that emerged in recent decades either happened or began in modern squares. He speaks of how this emergence of rioters corresponded to “an underlying political-economic unity, a material reorganization of society, which provide[d] them a shared set of problems and a shared arena in which to confront them.”

Charting the interconnectedness of capitalism, colonialism, and nationalism, Peter Linebaugh’s “Palestine & the Commons: Or, Marx & the Musha’a” speaks of “the violence of mapping, titling, buying, and selling which cast people into cities and camps following their expropriation from the land.”

Originally published in Kohl Journal, this interview is between Samanta Arango Orozco, a member of Grupo Semillas, and the artist Marwa Arsanios, who is co-convening with BAK the multi-chaptered project Usufructuaries of earth until 2 June, 2024.

A slow-growing table of contents for the Usufructuaries of earth online reader. The reader emerges, to begin with, as a constellation of archival texts assembled here through the “Usufructuaries of earth” focus on Prospections. Throughout the duration of Usufructuaries of earth project and beyond, diverse content—long reads, interviews, conversations, and visual interventions—will incrementally be (re)published into a public research and learning curriculum that studies histories and propositions of usufruct, of renewing shared practices of usership of and with earth.

“We are in the siege of a nature that has been hurt, divided, defiled, poisoned, harmed, and made to bleed,” writes Pelşîn Tolhildan, member of the Kurdish Women’s Movement.

Usufructuaries of earth is the first comprehensive exhibition of Marwa Arsanios’s work in the Netherlands. The exhibition foregrounds the artist’s collaborative approach to bringing together ecological, feminist, and decolonial knowledges and practices that put forward ideologies of usufruct, unhinging property-relations from the idiom of individuated possession and toward forms of common, more-than-human userships. Here is an audio tour of the exhibition given by BAK convenor of research and publications Wietske Maas.