Basecamp for Tactical Imaginaries: unbuilds and rebuilds cultural infrastructure to collectively confront the urgencies of today.Vanwege renovatiewerkzaamheden is het gebouw gesloten; op 8 september openen we opnieuw met een nieuw programma. Voor updates en aankomende evenementen, bezoek deze website.

Basecamp for Tactical Imaginaries: unbuilds and rebuilds cultural infrastructure to collectively confront the urgencies of today.Vanwege renovatiewerkzaamheden is het gebouw gesloten; op 8 september openen we opnieuw met een nieuw programma. Voor updates en aankomende evenementen, bezoek deze website.

Basecamp

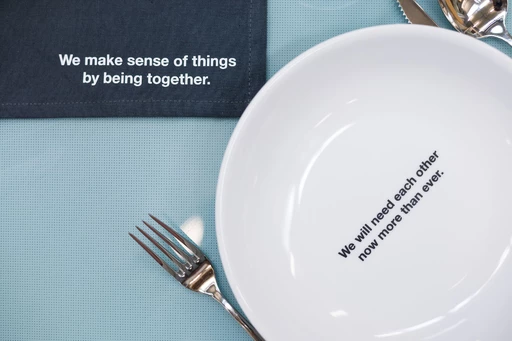

‘Basecamp voor tastbare verbeelding’ wil de crises van deze tijd gezamenlijk aanpakken, door te breken met én voort te bouwen op culturele infrastructuur.

De politieke, sociale, economische, en klimaat-crises van vandaag lopen in elkaar over en versterken elkaar. Om dit moment in de geschiedenis het hoofd te bieden is actie nodig. ‘Basecamp’ biedt, radicaal, de nodige culturele infrastructuur om je die actie voor te kunnen stellen. Verbeelding is onmisbaar voor een weerbare, vernieuwende, helende toekomst. Basecamp geeft de ruimte voor verbinding, uitdaging, ontdekking - en actie.

Programma

1 April 2025

30 June 2025

Programma

BAK presenteert Basecamp for Tactical Imaginaries: Building Cultural Infrastructure Anew

BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht staat aan het begin van een nieuwe fase en begint deze met een periode van zes maanden van denken en plannen.

1 January 2025

30 June 2025

Programma

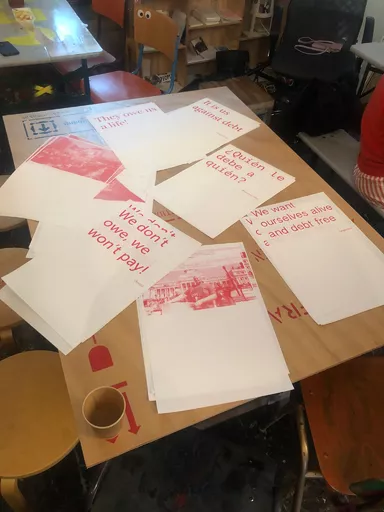

Climate Propagandas Congregation

Een tweedaagse bijeenkomst om gezamenlijk vormen van collectief overleven – in en ondanks de huidige uitstervingsoorlogen – te verbeelden en te propageren.

14 December 2024

15 December 2024