Author(s)

Verónica Gago and Lucí Cavallero

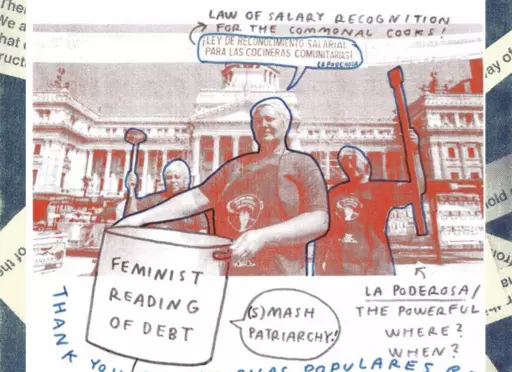

Three excerpts are republished here from researchers and activists Verónica Gago and Lucí Cavallero’s A Feminist Reading of Debt (London: Pluto Press, 2021). The text opens with a simple concept: that contemporary debt cannot be understood by only looking at “public debt,” and must instead look at the indebtedness present in everyday life. The authors call for debt to be adopted by social movements as a key issue, and furthermore, for people to be cognizant of the links between debt and sexist violence.

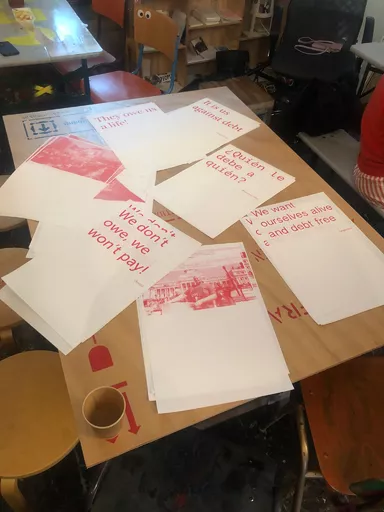

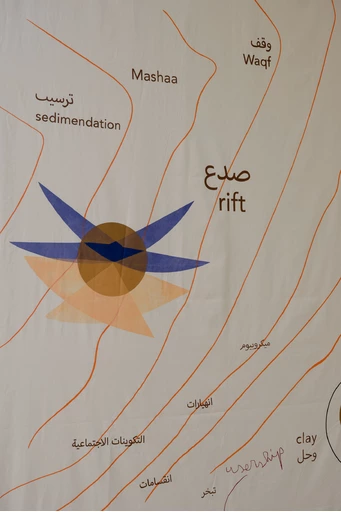

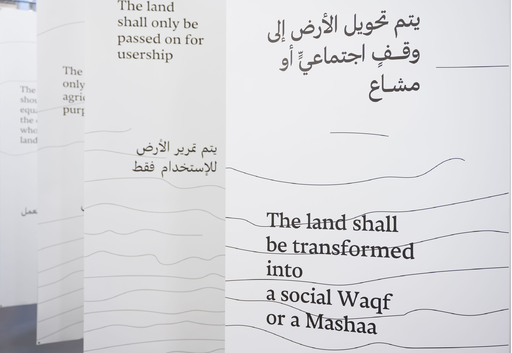

These excerpts are shared as part of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. It is one of the readings for the Rotterdam reading group “Undoing Debt”—convened by artists Iliada Charalambous and Philippa Driest—hosted by book and print workshop KIOSK on 28 April 2024. The reading group seeks to collectively unpack debt as a form of gendered and financial violence and see how, in turn, to “undo debt” through learning common political tools and vocabulary inspired by transnational feminist movements.

When we speak of debt, we place particular emphasis on private debt or what we will call indebted household economies (a term that we will problematize and broaden). Today, finance lands in household economies, in popular economies, and waged economies through mass indebtedness and it does so in ways that are specific to each one of those economies.

Our perspective is based on a tripartite wager. First, we want to highlight the fact that we cannot understand debt in its contemporary form only by looking at public debt (debt taken out by the state), while ignoring indebtedness in everyday life. Second, it is politically necessary for social movements and organizations to take the issue of debt into account in their resistance practices. And third, talking about debt in everyday life brings us to a strategic task: tracing the links between debt and sexist violence. By doing this, contemporary feminist struggles are leading a movement of the politicization and collectivization of the issue of finance. Lucía Cavallero and Verónica Gago, “Sacar del clóset a la deuda: ‘por qué el feminismo hoy confronta a las finanzas?’,” prologue to George Caffentzis, Los límites del capital. Deuda, moneda y lucha de clases (Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, 2018).

But, what is a feminist reading of debt? Here we start with a brief practical guide.

1. A feminist reading of debt proposes concrete bodies and narratives of its operation in opposition to financial abstraction.

Finance boasts of being abstract, of belonging to the sky of mysterious quotes, of functioning according to logics that cannot be comprehended by common people. It tries to present itself as a true black box, in which decisions are made in a mathematical, algorithmic way about what has value and what does not. By narrating how it functions in households, popular (largely non-waged), and waged economies, we defy its power of abstraction, its attempt to be unfathomable. That becomes clear in the interviews included in this book. Debt is a concrete mechanism that forces small agricultural producers to become dependent on agrotoxins. Debt is an expression of the rising costs and financialization of basic services. Debt is an apparatus that connects the inside and outside of prison, while prison itself is shown to be a system of debt. Debt is what you incur when abortion is criminalized. Debt is what drives popular consumption when exorbitant interest rates cause domestic life, health, and community bonds to explode. Debt is what enables illegal economies to recruit workers at any price. Debt incurred by young people, even “before” entering the labor market or in hyper-precarious jobs (since they are given a credit card along with their state benefits and first paycheck) appears as an apparatus of capture and precaritization of those very incomes. Debt is what provides basic infrastructure for life: health services that are inaccessible, supplies for when a child is born,

purchasing a motorcycle to be able to work in food delivery. Debt is a way of guaranteeing access to housing. Debt is the resource that appears when one is faced with emergencies and confronted by the loss of other support networks. Debt is a mechanism of generalized dispossession of migrant and Black populations. Debt is what ties together dependence on violent family relations.

2. A feminist reading of debt involves detecting how debt is linked to violence against feminized bodies. Drawing on concrete narratives of indebtedness, the link between debt and sexist violence becomes clear. Debt is what does not allow us to say no when we want to say no. Debt is what ties us to a future of violent relations from which we want to flee. Debt forces us to maintain broken relationships, which we continue to be locked into because of medium or long-term financial obligations. Debt is what impedes economic autonomy, even in feminized economies in which women play leading roles. At the same time, we cannot ignore its ambivalence: debt also enables certain movements. In other words, debt not only fixes in place; in some cases, it enables movement. We can think, for example, about those who go into debt in order to migrate. Or those who take out debt to start their own economic project. Or who take out debt to flee. But one thing is clear: whether as fixation or as the possibility of movement, debt exploits an availability to future work; it forces you to accept any type of work due to the pre-existing obligation of debt. Debt compulsively makes one have to accept more flexible labor conditions and, in that sense, it is an efficient apparatus of exploitation. Debt then organizes an economy of obedience that is nothing more or less than a specific economy of violence.

3. A feminist reading of debt maps and analyzes forms of work in a feminist register, rendering visible domestic, reproductive, and community labor as spaces of valorization that finance sets out to exploit.

The international strikes of women, lesbians, trans people, and travestis allowed for debating and making visible a map of the heterogeneity of labor from a feminist perspective. Based on diverse feminisms, a method of struggle emerged that corresponds to the current composition of what we call work, including migrant, precarious, neighborhood, domestic, community labor. That movement also produced elements for understanding waged labor in a new way and transformed how unions themselves organize. Adding the financial dimension allows us to now map flows of debt and complete the map of exploitation in its most dynamic, versatile, and apparently “invisible” forms. Understanding how debt extracts value from household economies and non-waged economies, those economies historically considered not to be productive, shows how financial apparatuses operate as true mechanisms of the colonization of the reproduction of life. It also demonstrates how debt enters into waged economies and subordinates them. Additionally, it allows us to understand how debt functions as a privileged apparatus for laundering illicit monetary flows, and, therefore, as the crucial link between illegal and legal economies.

We are interested in a feminist economics that involves a redefinition, based on diverse and dissident bodies, of what is considered labor and expropriation, of communitarian and feminized modes of doing in which popular, migrant, domestic, and precarious economies are disputed today. This feminist economics opens up a line of investigation about finance as a war against our autonomy Verónica Gago, “Is There a War ‘On’ the Body of Women? Finance, Territory, and Violence,” trans. Liz Mason-Deese, Viewpoint Magazine (2018), viewpointmag.com/2018/03/07/war-body-women-finance-territory-violence/. We use that to redefine what disobedience means in practice and, thus, to establish limits to neoliberal capitalism’s appropriation of our forms of life and desire.

We said that the feminist gesture in response to debt ultimately involves weaving together a refusal. The feminist strike has taken this question seriously by highlighting the connection between life, the feminization of labor, and financial exploitation. In other words: how do you carry out strikes and sabotage against finance? There are several practices that serve as a disobedient archive of “not paying.” Here we will comment on a few that seem inspiring to us.

In 1994, in Mexico, after a brutal devaluation of the Mexican peso in respect to the dollar caused inflation to increase to the point that it was impossible to pay off personal loans and dollarized mortgage payments, 30 percent of indebted people fell into bankruptcy. Activists from the movement known as “El Barzón” coined the slogan “I owe, I won’t deny it, but I’ll pay what is fair” to place the responsibility on the government and the banks for the increase in their debts.George Caffentzis, “Reflections on the History of Debt Resistance: The Case of El Barzón,” South Atlantic Quarterly 112, no. 4 (2013), pp. 824–830. The movement rapidly expanded throughout the country and forced the government to come to the aid of debtors.

In the heat of the Zapatista uprising and the recently implemented NAFTA, one of the first movements denouncing how the financial system abused and dispossessed small producers emerged. That denunciation inspired a wave of disobedience by debtors that expanded and emphasized how small peasant economies and household economies were being suffocated, and pointed out the connection between those debts and the pressure exercised by the debt of nation states.

In 2001, a debtors’ movement rose up in Bolivia, during the government of Hugo Banzer. Debtors occupied the Superintendent of Banks, the Episcopal Conference, and the Ombudsman’s Office, armed with dynamite. Oscar Guisoni (2012) recounted,

This “business of poverty” is detailed in the book by Graciela Toro that we referenced earlier,Graciela Toro, La pobreza: un gran negocio (La Paz: Mujeres Creando, 2010). published by Mujeres Creando, which emphasizes something that seems fundamental to us, especially in Latin America: the organic relationship between structural adjustment and microcredit, the state’s complicit role in usury, the role of international cooperation, and the link between debt and migrants as “the exiles of neoliberalism.” María Galindo, Las exiliadas del neoliberalismo (La Paz: Mujeres Creando, 2004).

Following the collapse of the financial bubble provoked by the real estate boom in Spain, in February 2009, the Platform for People Affected by Mortgages (PAH) emerged. That movement remains active today and has continuously denounced real estate speculation and how banks profit from mortgages, with the state’s support. They have carried out collective practices and direct action to stop evictions, functioning in many points across the country as decentralized groups. They have also highlighted the importance of the migrant and feminized composition of their organizers.

This movement has affirmed that the real estate oligopoly is what sustains accumulation by dispossession. With hashtags such as #WeAreStaying and #WeWillNotLeave, they denounce both real estate speculation under the financial impulse of loans that become unpayable as well as the increase in rents. They point to investment funds and large property owners as those directly responsible for the “expulsions,” referring to financial entities, owners of multiple properties, and vulture funds.

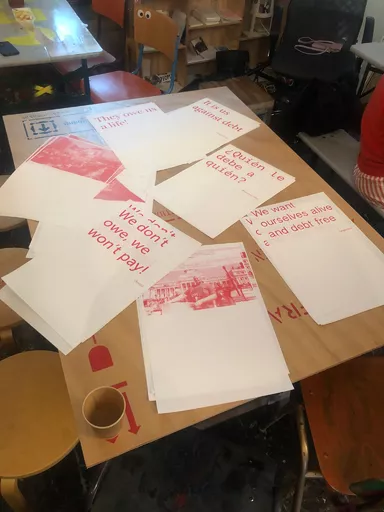

Inaugurating the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2012, different activists gathered in front of the New York Stock Exchange and camped in Zuccotti Park. There the slogan emerged “We are the 99%,” referring to a majority united by subjugation to debt that benefits the 1 percent of the world’s wealthiest people. There, a working group—Strike Debt—produced a manual of financial disobedience called “The Debt Resistors’ Operation Manual,” taking up the notion of the strike in its twofold meaning: to go on strike and to strike against. They also organized debtors’ assemblies and launched the “Rolling Jubilee” project that consisted of collectively buying students’ debt at reduced prices to pay it and liberate them.

Burning debt, closing abusive loan businesses, denouncing mechanisms of extortion, and practicing tactics of collective debt relief were some of the points that structured a fight against finance’s power of blackmail. They state it clearly in phrases that become slogans:

dimension of financial disobedience is also a struggle for public services, for recognition of labor that has historically been devalued and not remunerated by wages.Silvia Federici, “From Commoning to Debt: Financialization, Micro-Credit and the Changing Architecture of Capital Accumulation” (2016),cadtm.orgThat same type of diagram is what is drawn by the feminist strike.

A large assembly of women, lesbians, travestis, and trans people meets weekly in the neighborhood of Lugano. They are members of the Federación de Organizaciones de Base (FOB, or Federation of Grassroots Organizations), which is also part of the National Campaign against Violence against Women. The FOB is a social movement with an anarchist tendency that was formed in 2006. It brings together neighborhood political organizations from across the country. It is part of the piquetero, or unemployed

workers’ movement, and is defined by principles of direct democracy, self-management, class independence, federalism, and feminism. The majority of this assembly’s members are migrants and workers in cooperatives who do neighborhood cleaning or work in the organization’s print shop. We spoke to a few women in an assembly who told us how they are forced to take out debt because of inflation and austerity measures, and how that then forces them to accept jobs under ever worse conditions. But they also spoke of alternative forces of financing that help them to get out of debt. This conversation took place while preparing for the assembly to plan for November 26, a transnational day of action against violence against women, lesbians, trans people, and travestis. Debt was discussed as a form of economic violence and as part of the web of violence against which we organize ourselves.

We are part of a cooperative, we work cleaning the street. I also clean in a private home. However, since everything is so expensive now, it is not enough for us. We used to work less and I could get by.

Have you taken out any type of debt?

Not for now, I don’t want to because it is a big commitment. Now we are dealing with the issue of our house because our neighborhood is undergoing redevelopment and we don’t know if we will have to leave or if we will be able to stay and all of that. And with more debt, where could I get the money to pay for everything?

You see that in Ribeiro [household appliance store] when you take out debt and you don’t pay it back or if you are behind on a payment, they charge you tremendous interest. My uncle bought a television in Ribeiro, and that television, he paid double or triple, it was like buying three TVs.

Because he fell behind on the payments?

Yes and then the interest rate was very high.

Here I work in the cooperative and I am part of the printing press. I still don’t work anywhere else. I used to work more but I stopped because the truth is that now there isn’t even work anywhere else, and besides, threads are expensive. I worked in textiles and I also took out credit from Coppel [department store].

Coppel?

Yes, Coppel, I got some shoes that cost 1500 pesos and I fell behind with the payment and the debt multiplied, as if I were buying three pairs of shoes, that is, it tripled. That’s why now I don’t take out any more loans anywhere, not in Ribeiro or in Coppel. Because I have the cards. They offered me credit but I don’t do it because the truth is my life is very difficult now. There is a lot of poverty, the money from work is not enough. And also the Institute of Cooperative Housing is coming to my house, and I don’t know if I’ll get assistance, I don’t think I am going to get it. So I stopped a bit. Anyway, now they offered me a loan to build my house.

Who offered it to you?

I don’t know if they are from the housing office or what, but they offered it to me, and I told them no because I’m not in much of a hurry to build my house. I am going to do it calmly. I don’t want to be pressured to feel, “I owe money, I have to pay” and that’s why I didn’t take out a loan.

The money that you don’t have, that you need in order to live, how are you getting it?

I don’t know, I am supporting myself somehow. I don’t have children either. There is a lot of hunger and there are older women who are not united in any organization and now it is also very difficult to obtain a DNI [National Identification Document], which you need, because you have to pay 10,000 pesos. And then the truth is that they can’t join an organization because they don’t have a DNI and, yes they can participate to receive food, but they can’t join like we have.

And do you have any friends who are in debt?

Yes, in fact I have a compañera who got into debt like that and she had to pay.

She bought, I think, a stereo system and she couldn’t pay for it and she had to hand over all of her pasanaku to pay off her debt. The pasanaku is a type of savings between compañeras, like a loan but without interest. You need something and you get a number, that is, the money that we have rotates between us.

Pasanaku is a word that in Quechua means “pass the hand,” meaning you have to pass it around. Something that you get and you give in return. It is a game where you gather, let’s say ten people, those ten people get together and each month, depending on how you go about organizing it, it can be monthly, weekly, or biweekly. And you get together with those people and say, well “how much?” I put in 100 pesos, she puts in 100, another woman puts in 100. Here we raised 500 and we say each week we have to raise 500, we have to put in 100 each week. Then there is a lottery. It is a secret lottery, each woman takes out one number. You could end up with 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. The first week that we gather the 500, we give it to you. The second week it is her turn to take the 500; that is, you come with your 100 again, she comes with her 100, and so on.

Are all the women part of this?

Yes, since we are all compañeras.

We have organized among ourselves to play this way, each time that we get our monthly payment for working in the cooperative, we put a small part in the pasanaku.

Today, what is the pasanaku mostly used for?

To get out of debt, like my friend did, right?

A compañera was in debt and she used it all to pay it off?

Yes, to pay it off, so that they didn’t keep raising her interest payments.

And it works for you like that, if I draw number 5, when you all give me the $500, I can make a big purchase of something, an important product or something.

And you don’t go into debt, right?

Right, everyone receives the same amount and there is no interest or anything, because this way of doing things has been used for many years; in fact that is why we use the word pasanaku, it comes from Quechua. It has been used for years and years, I remember that my mom always played. Once my mom had gone into a ton of debt, she had put up the papers on my house and all of that.

Where had she gotten it?

There in Bolivia, in the Banco Unión.

What was it for?

It was to be able to start building a shack to live in. My mom had seven children and so we needed more space and she went into debt for that. And ever since that moment I have hated debt. I never bought anything like that in installments. Because they tell you that there is no interest and this and that, but when you finish paying and calculate how much you paid, the amount is much higher and there is interest involved.

Debt limits you in different ways because it affects your health, and you stop doing things in your free time to be able to generate more money. I know several people who have to constantly pay a certain amount of money each month and then the stress begins, the headaches, “where I am going to get money,” or “I’ll take out a loan from somewhere else to be able to pay and then I have to pay that,” and it starts eating up next month too. Thus, like always, it creates a never-ending chain. It is very complicated to live like that and it affects you in every way, because it also puts you in a bad mood, there is a lot of pressure. You put aside your children because you have to go out and earn money, that happens a lot.

And what type of jobs does someone get when they are in debt?

Under the table jobs, and on top of that, they pay you less, but it is better to earn a little than nothing at all. I have seen a lot of people like that.

When a person owes money to someone, sometimes the woman who loaned it is in need and then, what can she do? They clash, they argue, they fight. “You have to get it for me right now! Because I need it!” and sometimes the woman doesn’t have it. And where is she going to go? She has to go to someone else and perhaps she can’t obtain it and then she goes around feeling really bad, and sometimes her blood pressure rises, sometimes she is worried and doesn’t sleep. I also went through this with my mom. My mom, to put food on the table for us, had to borrow from a woman and sometimes it wasn’t enough and then she had to borrow from someone else and it wouldn’t be enough and it kept going like that.

That happened here?

No, that was in Bolivia, since we didn’t have a house, my mom paid rent, and sometimes she didn’t pay it and the woman kicked us out. That’s why I’m very sensitive toward people who are having a hard time here.

Where are the places where the financial companies offer credit?

In the neighborhood. They go to the school exit, for example.

They also go to the clinic where you take your children to the doctor or to the market where people are constantly circulating. It is like the neighborhood’s main street. And they go there and say, “you only need your ID card,” “you only need your ID card.”

I have seen Ribeiro and Coppel a lot recently, I have also seen Cencosud [retail company] a lot. Within the villa [slum], it is terrible.

Do they offer more to women or to men?

To us women.

And why to you all, do you think?

Because we are responsible for our homes and we are the ones who see what is needed in our households and that is why they come and offer more to women and they say “if you affiliate now, we will give you the card and you can go ahead and take out a certain amount.” They talk to you about amounts with which you can start to buy, “if you go ahead and take out the card now, next week you can withdraw what you want from the agency and you have an amount of 3000 or 4000 pesos to be able to spend and you’ll go about paying it off.”

They even give you pamphlets saying that as an affiliate you have a 20%, a 10% discount.

They sweet talk you more than anything, because it is not so much that you say “Oh, look I already have this and I am going to take some out.” Then the month ends and it’s not enough and then the problem comes, like she was saying, we get stressed, we have high blood pressure, because there is never enough money and this also affects our health a lot, as well as our families and everything. Because sometimes when a mother feels bad, then the whole house is no longer well, because the ones running the households are usually women.

Well one woman took out loans like that with a card and she went to pick up the products and then she couldn’t pay, and later her husband told her “you’re the one getting involved in those things, you bought things and now you can’t pay. Now deal with it.”

What did she buy?

A blender and a refrigerator.

That is why we help each other among women. For the pasanaku we all meet up in someone’s house and when the numbers are ready and all rolled up in a bag, then they come and see how many of us there are, say there are ten of us, then here are ten numbers. Then we place the ten numbers in the bag and everyone grabs one, they are sorted and you note them down. You see who drew 1, who drew 2, and so on, and you write everything down and every month you have to organize it so that everyone comes and brings the money to be able to collect it. And it is all collected.

And that is between women?

Some men also get involved.

And if there is a compañera who is very bad off economically, can some sort of exception be made?

If there is an emergency, the number can be exchanged for a closer one.

When it is her turn and she gives me the money that was going to be hers. And it’s always the same, because we already trust one another.

Because you have to be very committed. Especially if it lands on you the first round, you have to keep paying every month.That is why we do it between compañeras, I never had any problems.

Related

Held in the context of Usufructuaries of earth: chapter two, reading groups and publication, a reading group was convened by Iliada Charalambous and Philippa Driest on 28 April 2024 titled Undoing Debt, at KIOSK, Rotterdam. The reading group looked at debt as a form of gendered and financial violence and sought how to, in turn, “undo debt” through learning shared political tools and vocabulary inspired by transnational feminist movements.

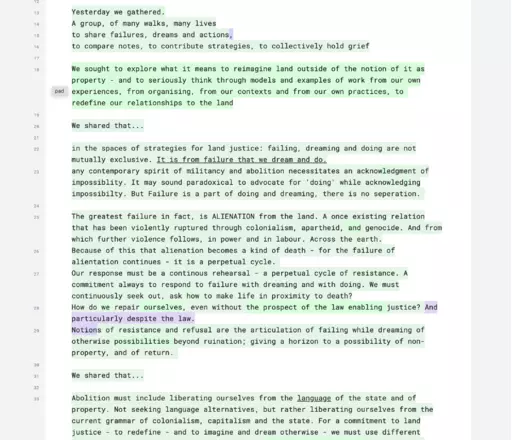

Convened by Johannesburg-based Yvonne Phyllis and MADEYOULOOK (Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho), the working session Failing, Dreaming, Doing: rehearsing abolition sought to conjure alternate imaginaries of life and labor with earth, beyond the regimes of colonial and racial enclosure. The following text was collectively written by the working session’s participants: Brenna Bhandar, Aya Bseiso, Layal Ftouni, Jennifer Irving, Tareq Khalaf, Gelare Khoshgozara, MADEYOULOOK (Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokgotho), Marie Nour Hechaime, Yvonne Phyllis, Philip Rizk, Bobby Sayers, Shela Sheikh, and Kasia Wlaszczyk and was read out by Nare Mokgotho as part of “PROPOSITION 3 Failing, Dreaming, Doing: rehearsing abolition” during the Usufructuaries of earth convention public program, Saturday 25 May 2024 at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht.

________________________________________________________________________________

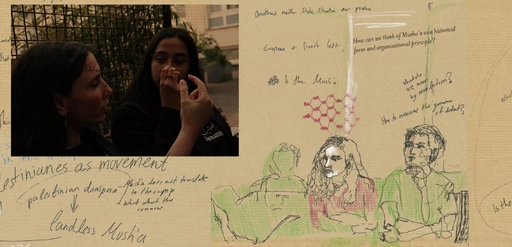

Held in the context of Usufructuaries of earth: Chapter two, reading groups and publication, a reading group spanning two days was convened by Joud Al-Tamimi and Lama El Khatib on 4 and 5 May 2024 titled And in your throats, a sliver of glass, a cactus thorn and On Value-Disrupting Activity, at bookstore خان الجنوب khan Aljanub, Berlin and Hopscotch Reading Room, Berlin respectively. Mokia Laisin put together a collaborative collage of annotations made during both days of the reading group discussions with input from Miriam Gatt on 4 May 2024.

Held as part of day two of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 25 May 2024, this video documents a closing conversation between Yvonne Phyllis, Denise Ferreira da Silva (online), Verónica Gago, Stefano Harney, Lena Wilderbach, and Brenna Bhandar (online), moderated by Shela Sheikh.

Held as part of day one of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 24 May 2024, this video documents the words of welcome by Maria Hlavajova, followed by a conversation between Marwa Arsanios and Wietske Maas—as means of introduction to the Usufructuaries of earth public program.

Held as part of day one of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 24 May 2024, this video documents a conversation between Brenna Bhandar, Yvonne Phyllis, and Ruth Wilson Gilmore(online), moderated by Layal Ftouni.

Held as part of day one of Usufructuaries of earth, chapter three, convention, on 24 May 2024, this video documents a conversation between conversation between Philip Rizk and Marwa Arsanios following a screening of Rizk’s film Mapping Lessons (2020).

This essay, “Enclosures from Below: The Mushaa’ in Contemporary Palestine,” from geographer and researcher Noura Alkhalili is shared as part of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. It is one of the readings for the Amman reading group convened by artist-led research group Bahaleen involving locally-invited artists and researchers.

This chapter, “Scholar-Activists in the Mix,” from Ruth Wilson Gilmore's Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation (2022) is shared as part of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. It is one of the readings for the Amman reading group convened by artist-led research group Bahaleen involving locally-invited artists and researchers.

This chapter, “Improvement,” from legal scholar Brenna Bhandar’s Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership (2018) is one of the readings for the Amman reading group.

In the context of Usufructuaries of earth: Chapter two, reading groups and publication, a multi-day roaming reading residency, convened by the artist-led research group Bahaleen is held from May 9–13 2024, along the hilltops of Jerash and the edges of Palestine—an hour’s drive from Amman. Invited artists and researchers join Bahaleen in traveling by car and on foot, navigating notions of access and return. Together they grapple with the possibilities of disruption and dissent, aiming to articulate a liberatory vision of the commons from within this geopolitical conjuncture. During the reading residency a board of images and sources were assembled as a harvesting. The images are shared below as screengrabs from this image board, with accompanying links where appropriate.

Originally published in Otherwise Worlds: Against Settler Colonialism and Anti-Blackness (Duke University Press, 2020), this essay, "Reading the Dead: A Black Feminist Poethical Reading of Global Capital" by academic, philosopher, and artist Denise Ferreira da Silva is shared here in the context of the project Usufructuaries of earth, co-convened by BAK with artist Marwa Arsanios. This chapter is one of the readings for the Berlin reading group convened by Joud Al-Tamimi and Lama El-Khatib, titled “On Value-Disrupting Activity,” at Hopscotch reading room, 5 May 2024. This reading group explores the political and theoretical stakes of value as it links to violences enacted on and through land and property in Palestine and elsewhere.

“What is a revolution that neither overthrows a state order nor institutes a lasting one of its own?” This is the question that teacher, author, and political theorist Nasser Abourahme poses in “Revolution after Revolution: The Commune as Line of Flight in Palestinian Anticolonialism.”

Three excerpts are republished here from researchers and activists Verónica Gago and Lucí Cavallero’s A Feminist Reading of Debt (London: Pluto Press, 2021). The text opens with a simple concept: that contemporary debt cannot be understood by only looking at “public debt,” and must instead look at the indebtedness present in everyday life. The authors call for debt to be adopted by social movements as a key issue, and furthermore, for people to be cognizant of the links between debt and sexist violence.

This is an extract from the chapter “Debt and Study,” in Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (2013). Across its three sections—Debt and Credit, Debt and Forgetting, and Debt and Refuge—this extract traces the sites and practices of “desired” and undesired debt that perforate contemporary financial capitalism and western culture. The text moves through different people who are marked as debt carriers, such as the precariat, the student, and racialized people, among others.

“Riot Now: Square, Street, Commune” is a chapter from political theorist Joshua Clover’s Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprisings (Verso, 2016). Taking the classical Greek agora—a place of assembly and commerce—as a starting point, Clover suggests that it is perhaps no coincidence that many of the riots and occupations that emerged in recent decades either happened or began in modern squares. He speaks of how this emergence of rioters corresponded to “an underlying political-economic unity, a material reorganization of society, which provide[d] them a shared set of problems and a shared arena in which to confront them.”

Charting the interconnectedness of capitalism, colonialism, and nationalism, Peter Linebaugh’s “Palestine & the Commons: Or, Marx & the Musha’a” speaks of “the violence of mapping, titling, buying, and selling which cast people into cities and camps following their expropriation from the land.”

Originally published in Kohl Journal, this interview is between Samanta Arango Orozco, a member of Grupo Semillas, and the artist Marwa Arsanios, who is co-convening with BAK the multi-chaptered project Usufructuaries of earth until 2 June, 2024.

A slow-growing table of contents for the Usufructuaries of earth online reader. The reader emerges, to begin with, as a constellation of archival texts assembled here through the “Usufructuaries of earth” focus on Prospections. Throughout the duration of Usufructuaries of earth project and beyond, diverse content—long reads, interviews, conversations, and visual interventions—will incrementally be (re)published into a public research and learning curriculum that studies histories and propositions of usufruct, of renewing shared practices of usership of and with earth.

“We are in the siege of a nature that has been hurt, divided, defiled, poisoned, harmed, and made to bleed,” writes Pelşîn Tolhildan, member of the Kurdish Women’s Movement.

Usufructuaries of earth is the first comprehensive exhibition of Marwa Arsanios’s work in the Netherlands. The exhibition foregrounds the artist’s collaborative approach to bringing together ecological, feminist, and decolonial knowledges and practices that put forward ideologies of usufruct, unhinging property-relations from the idiom of individuated possession and toward forms of common, more-than-human userships. Here is an audio tour of the exhibition given by BAK convenor of research and publications Wietske Maas.