Dilar Dirik Interviewed by Jonas Staal

Author(s)

Dilar Dirik, Jonas Staal

From: New World Academy Reader #5: Stateless Democracy, Renée In der Maur and Jonas Staal in dialogue with Dilar Dirik, eds. (Utrecht: BAK basis voor actuele kunst, 2015), pp. 27–54

New World Academy Reader #5: Stateless Democracy (2015), edited by Renée In der Maur and Jonas Staal in dialogue with Dilar Dirik, explores the foundations of the practice of stateless democracy in terms of politics, governance, science, and art from the perspective of the Kurdish Women’s Movement. The opening interview with Dirik, “Living Without Approval,” traces the history of the Kurdish movement to ancient Mesopotamia and its separation through colonial rule as the foundation for the rise of the women’s movement.

Dilar Dirik: One could start off by deconstructing the words “Kurdish,” “women,” and “movement.” Many people think that a national cause—a national liberation movement or nationalism—is incompatible with women’s liberation. I agree, because nationalism has many patriarchal, feudal, primitive premises that in one way or another boil down to passing on the genes of the male bloodline and reproducing domination, to pass on from one generation to another what is perceived as a “nation.” Add to that the extremely gendered assumptions that accompany nationalism, which affect family life, labor relations, the economy, knowledge, culture, and education, and it becomes evident that it is a very masculinized concept. The Kurdish Women’s Movement is named as such because of the multiple layers of oppression and structural violence that Kurdish women have experienced precisely because they are Kurdish and because they are women.

The Kurdish people have been separated historically over four different states: Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran. In each of these states, Kurdish women have suffered not only from ethnic and socioeconomic discrimination, but also suffered as women because of the patriarchal foundations of these states. At the same time, they have suffered oppression from within their own communities. The focus on their identity as Kurdish women hence draws on the violence directly related to this multiple marginalized identity. That is why the point of reference for the Kurdish Women’s Movement has always been that there are different hierarchical mechanisms, different layers of oppression, and in order to live with ourselves in a genuine way, we cannot liberate ourselves as women without also challenging ethnic, economic, and class oppression on all fronts.

In Turkey, for example, just as in the other countries, Kurdish women are often excluded from feminist movements. Turkish feminism was essentially founded on the secular nationalist model of the Turkish Republic: one flag, one nation, one language. So, despite having achieved many victories for Turkish women, Turkish feminists still subscribed to the nationalist dogma of the state, which does not accept the reality that there are non-Turkish people in the region as well. Kurdish women were consistently portrayed as backward and undeserving of the same type of education as Turks when they chose not to subscribe to the dominant nationalist doctrine. As a result, the Turkish state debased the struggle of Kurdish women by combining sexism and racism, claiming that women are used as prostitutes by the movement. It also proactively used sexualized violence and rape as systematic tools of war against militant Kurdish women in the mountains or in the prisons. Sabiha Gökçen, the adopted daughter of the founder of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, is exemplary of this contradiction. Although she is praised for being the first female pilot in Turkey, she is also the woman who bombed Dersîm (now called Tunceli) during the massacre on Kurdish Alevis in 1937–1938.

The word “movement” makes it clear that this is not just one party, one organization—it is everywhere. The most important part of this mobilization is its grassroots element, but it also has strong theoretical components: the Kurdish Women’s Movement is active where it needs to be active, without geographic restrictions. Part of its aim is also to mobilize different women in the region: to mobilize Turkish women, Arab women, Persian women, Afghan women, and so on. In 2013, the first Middle East Women’s Conference was initiated by the Kurdish Women’s Movement in Diyarbakır or Amed in Kurdish, a city in southeastern Turkey, the region the Kurds call Bakur, meaning northern Kurdistan. Women from across the region, from North Africa to Pakistan, were invited to build cross-regional solidarity. The Kurdish Women’s Movement is an idea: an idea to make sure that women’s liberation does not have boundaries and is regarded instead as a principle, as the fundamental condition for one’s understanding of resistance, liberation, and justice.

JS: Do you see a universal dimension to the struggle of the Kurds?

DD: Terms such as “Kurds,” “Arabs”—these are open for contestation. Many people have argued about what makes a Kurd. Is it the language? The geography? In my eyes, Kurdish people and in particular Kurdish women embody the multi-layered oppression of many peoples who have been subjected to various forms of colonialism. So the oppression of the Kurds is shared by many other peoples, but the Kurds have dealt with the exceptional marginalization of their peoples by not one, but four states. The Kurds, apart from those in Iraqi-Kurdistan, have had little to no international support—I refer here mainly to the leftist, radical wing of the Kurdish movement. Not only have the Kurds expressed their solidarity and support for many other stateless struggles in the world, but their own extreme oppression and resistance appeals to colonized and oppressed people all over the world in an almost universal sense. The ways in which communities across all continents have claimed the resistance of Kobanê as their own cause, for instance, demonstrates the universal character that this struggle can take.

JS: What is the foundation of colonialism in the region and how did this inform the critique of the state in the Kurdish Women’s Movement?

DD: There have historically been different systems sharing the same hierarchical premises of subjugation, domination, and power prior to the current nation-state system. The concept of the modern nation-state is still relatively new; it’s only a few hundred years old. In the Middle East, there used to be empires, different sorts of regimes, but not in the sense of the nation-state as such: people of various religious and ethnic groups lived together, with different hierarchies and social orders in place. The world’s current dominant system is rather primarily based on people forming one collectivity, unity through monopoly, established and restricted through the terms and borders determined by the nation-state, and having emerged in parallel to the rise of capitalism and the stronger, formal institutionalization of patriarchy.

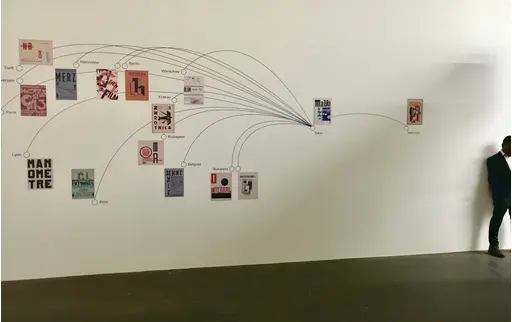

Indeed, European colonialists forced the concept of the nation-state upon the Middle East, but the notion also resonated with certain elites in the region who saw it as an opportunity to assert their power by breaking with former hierarchies and elites. I will henceforth focus on the region of Mesopotamia where the Kurdish people live. Before the establishment of current state borders, which are less than a hundred years old, there were the Ottoman and Persian empires; in the seventeenth century, Kurdistan was initially divided between these two. In the early twentieth century, when the Ottoman Empire began to collapse and the European governments were fighting Atatürk’s army, the Sykes–Picot Agreement 1 divided borders along colonialist interests. Some of these borders were literally drawn with rulers, thus blatantly illustrating the arbitrary imposition of imagined constructs like the nation-state, which violate and deny the more fluid and organic realities on the ground.

This is colonialism: the forced imposition of borders that do not reflect the realities, loyalties, or identities on the ground, but are based solely on western (or other non-local) interests. It was done in a very insidious way, because those living in the region were made to believe that they themselves would rule these newly carved out regions. This is an example of colonialism that operates by giving colonial power to somebody else who will colonize the people by proxy. From a distance, it will appear as if the people of the Middle East are determining themselves. In 1923, following the decline and eventual collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Turkish Republic was founded. When plans were being developed to found this new republic, the Armenian Genocide took place to essentially clear space for this new state. The Kurds played an active role in the genocide, and this is something they have to come to terms with. The Kurds were promised rights in this new state, but were later struck by the same oppression.

The creation of the Turkish state was an attempt to copy the French model of the secular republic. Yet this was not secularism in the true sense of the idea, as Alevis, Christians, and Yezidis in the region were subjected to assimilation, discrimination, and massacre by the Turkish state. The Sunni-Muslim national identity was predominant, in spite of the secularist pretentions of the republic. This nationalist conception of modernity exposes the real backwardness and oppressive, fascist foundations of the Turkish state. This alleged modernity was built on blood: systemic ethnic cleansing, historical denial, and forced assimilation.

The Turkish Republic wanted to wipe out the identity of the Kurds and thus removed all references to Kurdish culture and Kurdistan from its history books. This occurred hand in hand with psychological warfare, with the state alleging that there are no Kurds, that the Kurds are in fact “mountain Turks.” It was a politics of denial, and when the Kurds inevitably rose up against it, they were met with harsh measures.

JS: What was the position of the Kurds in other states, like Syria, Iraq, and Iran?

DD: In countries like Iraq and Syria, both ruled by Ba’ahtist regimes, there was an active politics of Arabization in place. These states did not deny the Kurds in the same way as Turkey, but they oppressed them nonetheless by taking away their rights to citizenship, forbidding their language, and repressing all political activism. Areas historically inhabited by Kurds were resettled with Arabs. The Kurdish language was not taught, meaning that in order to be literate and educated, Kurds had to learn Arabic. Several massacres were committed by these states, the most notable one being the chemical weapons attack ordered by Saddam Hussein in 1988 on Halabja, during which 5,000 people lost their lives within a short few hours.

Many Kurdish parties were also active during the Iranian Revolution of 1979. They wanted to be part of the revolution, which was initially vanguarded by leftist student groups that opposed the Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi. But when Ayatollah Khomeini took over, he issued a fatwa against the Kurds that made it permissible to kill them. Thus, the expectations of the Kurds, like the expectations of other oppositions, were hijacked during the revolution.

The Iranian state is nonetheless extremely multiethnic. The “minorities” in Iran are huge, and they consist of several millions of people—the Ahwaz, Azeri, Kurdish, and Baluch peoples, among other groups. This is why Iran cannot simply deny all of these different peoples and their different languages, at least not in the same way as Turkey had. The politics of Iran are based on a very chauvinist Persian doctrine. The Iranian regime did not deny the identity of the Kurds, but considered itself superior to it. Compared with Kurds in other regions, the Kurds in Iran were better able to preserve most of their culture, heritage, and art, because the Iranian state never denied them these cultural rights. Rather, they deprived Kurds of political rights: the right to politically organize and the right to political representation. Iran regularly executes political prisoners of different ethnic groups, including many Kurds. Women suffer another layer of oppression due to the theocratic nature of the Islamic Republic.

JS: This systemic denial of political rights has created the base for a strong Kurdish nationalist movement.

DD: Most, if not all, of the Kurdish parties in the four regions started with the aim of an independent Kurdish state. The idea was that we suffer this oppression precisely because we are stateless, and so if we—the “largest people without a state”—have a state of our own, our people would no longer encounter such large-scale systemic violence.

This kind of nationalism often emerges in colonial contexts. However, state nationalism is very different from anti-colonial movements that claim a national identity in order to assert their existence in the face of genocide. I am critical towards those who place Turkish, Iranian, or Arab nationalisms on the same level as Kurdish nationalism: you cannot claim this without taking into consideration the radical unequal power relations that are at the foundations of this conflict. Yet this does not mean that nationalism is the solution or that a Kurdish state would pave the road toward genuine self-determination.

JS: This idea also contributed to the creation of the Marxist-Leninist Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), founded by Abdullah Öcalan in 1978, which led to the necessity of waging armed struggle against the Turkish government’s repression of the Kurds. At a certain stage, the PKK’s leadership changed its ideas concerning the goal of achieving an independent state.

DD: Indeed, the PKK started out with the aim of an independent nation-state as a reaction to state violence and systemic denial, assimilation, and oppression. It emerged at a very conflict-ridden time in Turkey. In 1980, four years before the PKK began its armed struggle, a military coup d’état in Turkey had tried to wipe out the left and other oppositional groups. The PKK experienced many ups and downs, related to the guerilla resistance against the Turkish army, the fall of the Soviet Union, the collapse of many leftist liberation movements, and Öcalan’s capture in Kenya on 15 February 1999, organized by the Turkish National Intelligence Organization in collaboration with the United States’ Central Intelligence Agency. It was in this context during the course of the late nine-ties that the PKK began to theoretically deconstruct the state, fueled in part by the Kurdish Women’s Movement, having come to the conclusion the state is inherently incompatible with democracy.

Statelessness exposes you to oppression, to denial, to genocide. In a nation-state oriented system, recognition and the monopoly of power are reserved for the state and this offers some form of protection. But the point is that the suffering of the stateless results from the system being based on the nation-state paradigm. When you gain the monopoly on power, your problems are not instantly solved. Having a state does not mean that your society is liberated, that you will have a just society, or that it will be an ethical society.

The question is more systemic: Should we accept the premises of the statist system that causes these sufferings in the first place? Could we have a nation-state, a concept inherently based on capitalism and patriarchy, and still think of ourselves as liberated? In the Middle East, absolutely no state is truly independent. China, Russia, the US, and European governments: they are the ones hierarchically controlling the international order.

This shift away from desiring a state was an acknowledgement that the state cannot actually represent one’s interests, that the monopoly on power will always be in the hands of a few people who can do whatever they want with you, specifically because the state is implicated in several international agreements, including the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. That is why the PKK began to understand the importance of rejecting top-down approaches to power and governance. It concluded that there needed to be political structures that could serve the empowerment of the people, structures that would politicize them to such a degree that they internalize democracy. The work of the Kurdish Women’s Movement was pivotal in that process. Patriarchy is much older than the nation-state, but nation-states have adopted its mechanisms. That is why the disassociation of democracy from the state is also a disassociation from patriarchy.

JS: When I first met Fadile Yıldırım, an activist of the Kurdish Women’s Movement, at the first New World Summit in 2012, she said that the struggle of the Kurdish Women’s Movement is twofold. On one hand, it is a struggle against the Turkish state and its re-pression of Kurdish culture and history; on the other hand, it is a struggle within the PKK itself for the acknowledgment of women as equal fighters to men.

DD: In national liberation movements, there is always the danger that women’s rights will be compromised following liberation. Women were part of the PKK from the beginning. Some of its key founders, like the late Sakine Cansız, were women. The PKK started out in university circles where people were exposed to socialist ideas; such circles easily accepted the concept of women’s liberation. When the PKK started to wage its guerilla war in 1984 and its grassroots element began to take full force, many people from the villages and rural areas—people with little to no education—joined the struggle. The presence of people from different socioeconomic backgrounds exposed many class divisions at the early stage of the movement. Moreover, due to their different back-grounds, the people who came from the villages were more reluctant to accept women as equals to men.

As a result, women were pushed a big step back. While in the beginning the mobilization was very ideological and theoretical, when the war intensified, its ideological and educational elements were often pushed to second place. At that time, women actually began to cut their hair very short to appear more masculine: the idea was to copy men in order to prove that they were equally capable.

In the nineties, with encouragement from Öcalan, women who experienced discrimination within their own ranks began to mobilize. Öcalan has always been supportive of women’s liberation and has contributed significantly to the theoretical justifications around the autonomous organization of women within the PKK. Because of this, however, he has also faced opposition. The nineties saw the initiation of the Kurdish Women’s Movement, but in the last ten years, the movement has gained much more strength. Contradictions such as class divisions have been tackled and new approaches towards women’s liberation have been adopted in order to transform women’s liberation from an elitist ideal to a grassroots cause.

In 2004 the PKK experienced a major backlash, with many people actually talking about the end of the organization. This was at the same time when major international offensives against the PKK began. Furthermore, Öcalan’s brother, Osman Öcalan, caused a major split in the movement by taking a feudal-nationalistic line. One of Osman Öcalan’s slogans was “We want to be able to marry too,” because in the PKK, the cadres and the guerillas are not allowed to marry or have sexual relationships due to their militancy.

Osman Öcalan’s stance was perceived as an explicit attack on the women’s movement. Many women broke away from the PKK, and some married men in the circles around Osman Öcalan. The morale of the women’s movement suffered severely at this time because of the perception that Kurdish women should just behave like “normal” wives. To be clear, the women’s movement doesn’t oppose marriage as such; the problem was the way that Osman Öcalan tried to undermine the women’s movement by saying that their militancy, and thus their liberation, was not “normal.”

Ever since, the women’s movement has restructured itself to create new organizations. Now, its main body is the Women’s Communities of Kurdistan (KJK). The aim is to form an umbrella organization, rather than a single, decisive party. This could include the women’s branch of a particular party, a women’s cooperative, or a women’s council in Europe, to name but a few possibilities. Regardless of the forms such cooperating institutions might take, they are all part of one large movement. Today, due to this massive mobilization, the whole world is talking about the Kurdish Women’s Movement, not least because of its resilience against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

JS: You have described how the Kurdish Women’s Movement and Abdullah Öcalan critiqued the state as being inherently anti-democratic, due to the patriarchal relations it embodies and its complicity in the structures of global capital. In Öcalan’s prison writings, he refers to the political alternative as “democratic confederalism,” which is essentially a form of democracy without the state, and based instead on self-governance, communal structures, and gender-equal political representation. How did the Kurdish movement respond when he articulated this radical proposal?

DD: Öcalan declared the ideal of democratic confederalism in 2005, while still in prison. As I said, at that time he had already rejected the strife for the Kurdish nation-state. For a movement comprising millions of people who anticipated an independent state, this concept of democratic confederalism was initially very difficult to grasp. It is difficult to reach the grassroots with the idea of a democracy without the state. In fact, many have accused Öcalan on abandoning the cause of “independence,” because they understand independence only within the framework of the state. It is very important to bear in mind the different realities and consciousness of people within the movement. In recent years, however, and through active practice, the notion of democratic confederalism has begun to resonate with many people.

The PKK and affiliated organizations managed to introduce the concept of democratic confederalism through council movements, autonomous organizations, communities, and alternative schools in Turkey. In other words, models of self-organization—central to the idea of democratic confederalism—were used to communicate that very same concept to the masses. Through active practice, they showed that an alternative to the state was in fact possible. Essentially, this boils down to teaching politics through practicing politics—to radically over-come the separation between theory and practice.

You need to cooperate with all people who are interested in democracy, because the concept of democratic confederalism is not just to liberate yourself by establishing autonomy in spite of the state, but also to democratize existing structures. For example, in Turkey, despite state repression, the Kurdish movement established the principle of co-presidency: the idea that each political organization should have a male and female representative. Gender equality on all levels is one of the foundations of democratic confederalism, but one can put it to practice directly not only in autonomous regions, but also in existing political structures. You have to lead the way through practice.

JS: At what level is democratic confederalism a political blueprint, and what are its inspirations?

DD: Öcalan reads a lot in prison. It was there that he encountered, among others, the work of the American anarchist and radical ecologist Murray Bookchin, who had developed the concept of “communalism”: self-administration without the state, in rejection of centralized structures of power, reminiscent of the early Soviets and the 1936 libertarian-socialist Spanish Revolution in Catalonia. Öcalan recognized that Bookchin’s concepts, such as that of “social ecology,” resonated with the Kurdish quest for alternatives to the state. This was not just an ecology in terms of nature, but also the ecology of life: the foundation of non-centralized, diversified, and egalitarian structures of power which link to questions of economy, education, politics, co-existence, and the importance of women’s liberation. What is explicit in both Bookchin and Öcalan’s thoughts is the idea of working “despite of” what is happening around you—in other words, to act through practice. But Bookchin is not the only foundational thinker who shaped Öcalan’s thoughts; in his writings, he references Michel Foucault and Immanuel Wallerstein, among many others.

Democratic confederalism is built on the work of many thinkers, but it is customized to the particularities of the oppression that takes place in Kurdistan. It considers the question of how to build an alternative to the state—for and by the people—independent of the international order, while also taking into account the specific oppressive regimes of the region. This is why the insistence is always on regional governments and regional autonomy, even though the model of democratic confederalism is proposed for the entire Kurdish region. Each region has to discover what works best for it, all the while adhering to the principles of gender equality, ecology, and radical grassroots democracy. These are the pillars of democratic confederalism that stand beyond dispute.

JS: The model of democratic confederalism has recently found its full implications in the northern part of Syria, in the so-called Rojava Revolution, led by Kurdish revolutionaries. Could you explain what the Rojava Revolution is?

DD: Rojava is the Kurdish word for “West,” referring to West Kurdistan, or if we look at the present geopolitical map, it is the northern part of Syria, which knows a large population of Kurds. The Rojava Revolution was triggered by the so-called Arab Spring uprisings of 2012, but the origins and background of the movement go back much further. The Kurds had opposed the Syrian regime for a long time. Already in 2004, there was the Qamişlo massacre, during which Assad’s regime killed several Kurdish activists involved in an uprising. Under the Assad regime, the Kurds had no rights to citizenship and they were not allowed to speak their language. In many ways, their situation was much worse than the Arab opposition, and so they naturally took part in the general uprising in 2012. The Kurds soon realized, however, that the opposition would not necessarily provide them with better alternatives, as they were manipulated by western and non-western actors who were driven by their own self-serving interests in the fall of Assad rather than a true investment in a Syrian democracy or aiding the liberation of the people. As a result, more and more radical fighters were supported and imported by foreign forces. Today we know them as part of ISIS.

The Assad regime engaged in heavy clashes with the Free Syrian Army, the main opposition group, in areas like Damascus and Aleppo. As a result, the regime with-drew from the Kurdish areas in the northern part of the country, and the Kurds took their chance to take over: they at once seized control of the northern cities, and replaced the institutions of the Assad regime with their own new system. On 19 July 2012, the Rojava Revolution was declared. Turkey was very angry, not only because it has a long border alongside the Kurds in Syria, but even more so because the Rojava Revolution is ideologically linked to the PKK. At that exact moment, the Turkish government announced that they would start peace negotia-tions with the PKK: they had to respond to the pressure. Then, on 9 January 2013, three female Kurdish activists were killed assassination-style in Paris: Fidan Doğan, Leyla Şaylemez, and Sakine Cansız, the latter being a co-founder of the PKK. For the Kurdish community, it was clear that the murders were a desperate attempt by Turkey to weaken the Kurds’ negotiation power, to show that they could serve a blow to Kurds even in Europe. Meanwhile, the Rojava Revolution faced several enemies: first it was the regime of Assad, and then emerging jihadist groups, such as the Jabhat al-Nusra or al-Nusra Front, an organization explicitly supported and funded by the Turkish state to undermine the autonomous structures of the Kurdish resistance. After that followed the organization that calls itself ISIS.

Towards the end of 2012, despite the fact that they had to fight these jihadist forces, the Kurds have started to found their own autonomous administrations and councils and built alliances with parties from all over the region. In November 2013, the Revolution of Rojava declared its autonomy: it no longer operated within the state.

The situation grew increasingly difficult, as the whole world was being dragged into the war: the US, Europe, Russia, the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, Turkey, Iran… It became something of a second Cold War. Assad fighting the rebels was just a microcosm of all the international interests that were invested in the region. Due to Turkey’s NATO membership and their interests in top-pling both Assad and Kurdish autonomy, the Kurds were not invited to the so-called Geneva II Peace Conference on Syria in January 2014, which was supposedly intended to find a solution for the conflict in Syria. If this had really been a genuine attempt to bring different parties together to find a solution, it would have been a no-brainer that the Kurds, who make up 10–15 percent of the population and who emerged as key actors in the war, should be invited. The so-called opposition was hand-picked by the powers that wanted to get rid of Assad. This is not meant as an apology for Assad—Assad had to be toppled—but one cannot simply construct an opposition for one’s own interests. The results of the conference, similar to many other major international decisions, did not at all reflect the will of the Syrian people and it certainly did not aim at a democratic solution.

The independent cantons of the autonomous region of Rojava, modelled after democratic confederalism, were announced at the same time that the Geneva II convention took place. So, basically, the response of the Rojava Revolution was: “Well, if you don’t invite us to Geneva II, to this major international conference, we announce our cantons; we claim our full independence with or without your approval.” This is the general stance of democratic confederalism, this is what it is all about: to work together and move forward no matter what is happening around you.

After this, jihadist attacks on Rojava only intensified. There were reports of jihadis being treated in Turkish hospitals. Had the world listened then, several massacres could have been avoided. Salih Muslim, the co-president of the main political party of Rojava, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), was denied visas four, five times to travel to the US to explain the threat of state-sponsored terrorism in the region. Sinem Mohammed, a prominent TEV-DEM representative, did not receive a visa to the United Kingdom, all because of outside political interests. On top of all of this, there are several economic and political embargoes on Rojava. In 2014, even the Kurdish Regional Government of Iraq collaborated with Turkey in an attempt to marginal-ize the Rojava Revolution, because they wanted to be the dominant Kurdish force in the region. It is remarkable that the Rojava Revolution even happened and persisted in spite of these obstacles. Such obstacles actually account in part for why Rojava has been so successful, for had it been co-opted by a wider force, with very undemocratic interests, it might not have become a genuine revolution.

JS: That is to say that the revolutionary conditions that made it possible for the Rojava Revolution to develop were also partly due to the denial of the international order, which forced the cell-like struc-tures of the Kurdish resistance to strengthen and become even more sophisticated?

DD: Exactly. It was a completely self-sustained effort—there was no support from anywhere. The revolution had to work in spite of this war and embargoes, so people had to come up with creative solutions. The People’s Defense Units (YPG) and Women’s Defense Units (YPJ), the self-organized armed forces of Rojava, even had to build their own tanks! The Syrian regime often used to say that certain products cannot grow in Rojava, but through experimentation, people learned that many vegetables actually grow very well in Rojava and have since created sustainable agricultural projects. This general self-reliance proved successful over the course of the revolution, especially as the fighting forces of Rojava handled their defense by themselves rather than relying on weapons or instructions from abroad.Of course, it would have been great to have had support, but only from the right places—from leftist movements and parties, for example. Yet the fact that there was no outside support also nurtured the politicization of the people, who learned to do everything on their own. But the costs and sacrifice were very high.

1 The Sykes–Picot Agreement, signed on 16 May 1916, was an undisclosed agreement between the governments of the United Kingdom and France, with support of Russia, which mapped out the respective governments’ proposed spheres of influ-ence in the Middle East. The agreement was made in anticipation of the Triple Entente’s defeat of the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

Related

The modern nation-state is supposed to be ethnically and culturally homogenous; after World War II, both Israel’s implementation of Zionism and Arab Nationalism adopted versions of this purism—purging and excluding from the body social what refuses assimilation.

As part of FORMER WEST: Documents, Constellations, Prospects, 18–24 March 2013 at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, art critic, poet, and curator Ranjit Hoskote convened a forum on “Insurgent Cosmpolitanism” with cultural theorists and artists whose work addresses and performs the insurgent cosmopolitan condition.

Mariana Botey’s text The State Is Coagulated Blood and Bones is written as a prologue to Cooperativa Cráter Invertido’s codex-comic Sangre Coagulada y Huesos (Coagulated Blood and Bones, 2021). The two contributions have been conceived in collaboration and are to be read in parallel, allowing for a mutual disruption of discourse and image.

Long weaponized in the service of capital by the agents of neoliberalism, the nation-state is once again upheld as the bulwark of a white ethnos, securing privilege against migrants and immigrants, and against other nation-states in relations of neocolonial dependence.

From: New World Academy Reader #5: Stateless Democracy, Renée In der Maur and Jonas Staal in dialogue with Dilar Dirik, eds. (Utrecht: BAK basis voor actuele kunst, 2015), pp. 27–54

From: Once We Were Artists, Maria Hlavajova and Tom Holert, eds. (Utrecht: BAK, basis voor actuele kunst and Amsterdam: Valiz, 2017), pp. 32–52

In 1970–1971, Guyanese radical historian and anti-colonial activist Walter Rodney gave a series of lectures on the historiography of the Russian Revolution at University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Inspired by C. L. R. James’s historical work on the October Revolution, Rodney set out to reveal the parallels between the problems confronting the postcolonial regimes in Ghana and Tanzania, and those that the Bolsheviks faced in building the Soviet state.

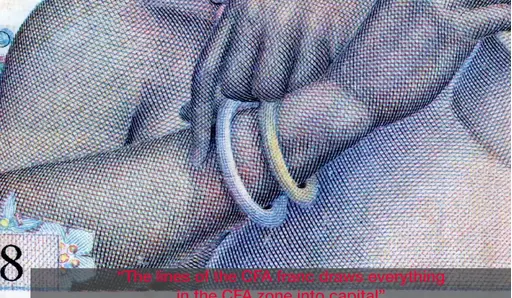

The video The Cut, The Punch, The Press (2021) is assembled from filmed fragments of a collection of 65 banknotes of the CFA franc, circulated between 1945–2021.