In his 1860 study The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, historian Jacob Burckhardt noted that with the Italian city-states of the Renaissance, “a new fact appear[ed] in history: the state as the outcome of reflection and calculation, the state as a work of art.” 1 Writing during World War II, the philosopher Ernst Cassirer—familiar with Burckhardt—continued in a similar vein, arguing that circa 1500, with Macchiavelli, “the state [had] won its full autonomy . . . but at the same time it [was] completely isolated.

The sharp knife of Macchiavelli’s thought [had] cut off all the threads by which in former generations the state was fastened to the organic whole of human existence.” 2 Cassirer stresses that “what Macchiavelli wished to introduce was not only a new science but a new art of politics. He was the first modern author who spoke of the ‘art of the state.’” 3 Here, “art” is used in the sense of “techne,” of a technical skill set. Today, when the artist Jonas Staal writes about “the art of creating a state” and “the art of the stateless state,” he blends such early notions of statecraft with later Romantic and avant-garde conceptions of art.

The notion of the nation-state is commonly associated with the “Westphalian” system enshrined by the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, but this is only one (crucial) moment in the development of the art of the state. With Burckhardt and Cassirer, one could look to Renaissance Italy for certain crucial theoretical elaborations that were necessitated by the precarity of its small-city states—frequently riven by inner discord and invaded by the territorial states of France and Spain, which turned various Italian cities into their proxies. This suggests a need to go beyond Burckhardt and Cassirer’s humanist fetishization of Renaissance Italy in the fifteenth and early sixteenth century. Recently, political theorist Mahmood Mamdani has focused on Spain during this same period, and particularly on the double event of 1492: the expulsion of the Spanish Jews and Moors (i.e., ethnic cleansing) and Columbus’s “discovery” of the New World (i.e., colonization). For Mamdani, it is this rather than the Peace of Westphalia that is the decisive moment for the development of the modern state. “Westphalia” merely inaugurated a regime in which the European states “tolerated” minorities at home while developing a necropolitical program in the colonies. 4

Around 1800, a further mutation of (nation-)statecraft occurred that would have profound consequences in Europe as well as “overseas.” The French Revolution’s designation of “the people” as sovereign raised the question of who is, and who cannot be, a full member of the people. Romanticism’s answer was to idealize an organic and ethnically homogenous Volk as the biological body of the state. The Romantic reaction against Napoleon, coupled with racist ideology in the service of colonial dominion, led to an enshrinement of ethnonationalism and white supremacism in state apparatus. The potency of this construction, which was glossed over rather than addressed and dismantled by various high-minded universalisms, has once again become apparent in recent years.

Under neoliberalism, democratic nation-states have long been hollowed out by those whom abolitionist scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls “anti-state state actors,” i.e., the people and organizations (think tanks, political parties, etc.) who use anti-state rhetoric to take hold of the state apparatus and impose privatization programs—including hefty corporate subsides, while the welfare system is being dismantled. 5 Trumpism, the Brexit campaign in the United Kingdom, and AfD in Germany have seen members of the financial and political elite taking the anti-state rhetoric in Völkische, white nationalist, and fascist directions—promising disaffected white voters that they will be “retaking control” of the state, even while dismantling whatever curbs on corporate interests were still in place.

BAK has responded to the renewed rise of nationalism and rebranded fascisms in its Propositions for Non-Fascist Living (2017–ongoing) series, while engaging with the ongoing and intensifying problematization of the state in contemporary theory, art, and activism with projects such as Call the Witness (2011), New World Academy (2013–2015) with Jonas Staal, FORMER WEST (2008–2016), and Once We Were Artists (2017). As an editorial series on BAK’s Prospections platform, “ExitStateCraft” will publish archival materials from these projects alongside new contributions.

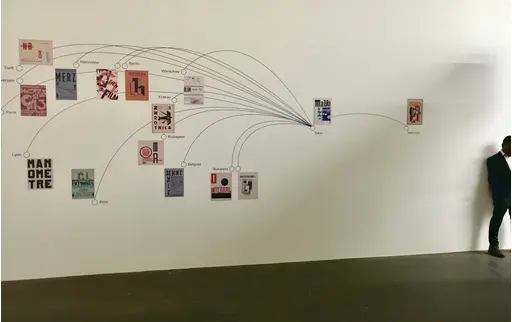

Rather than touting the latest shiny gizmo on the marketplace of radical theory, “ExitStateCraft” positions itself as part of an ongoing conversation. It resonates with recent projects such as iLiana Fokianaki’s Extra States: Nations in Liquidation (ExtraCity, Antwerp, 2018), and its title is an appropriative nod to Keller Easterling’s book Extrastatecraft (2014) and Hito Steyerl’s video installation ExtraSpaceCraft (2016). 6 Easterling’s portmanteau refers to the “often undisclosed activities” taking place in the “infrastructure space” of globalization, in an age in which global finance capital trumps and transforms the nation-state, resulting in sites “of multiple, overlapping, or nested forms of sovereignty, where domestic and transnational jurisdictions collide.” 7 Steyerl has written a compelling essay about freeports—zones for tax-exempt storage and sale of assets, including artworks—as a prime example of capitalist Extrastatecraft, but her installation ExtraSpaceCraft focuses on a different kind of free zone. 8 The piece presents a docufiction in which autonomous drone shepherds fly their “flock” over the Iraqi part of Kurdistan; alongside Chiapas, Kurdistan has become a key site of emancipatory ExitStateCraft.

Even (and especially) in a situation of waning state sovereignty, there are theorists who insist that “states remain a, if not the crucial emblem of political belonging and political protection,” and that the “plight of refugees and other stateless peoples is a reminder of the extent to which states remain the only meaningful sites of political citizenship and rights guarantees.” 9 Some stateless people and peoples beg to differ. As Dilar Dirik, a scholar and activist in the Kurdish Women’s Movement, put it in conversation with Staal in New World Academy Reader #5: Stateless Democracy, edited with the Kurdish Women’s Movement, Kurdish activism has shifted away from “desiring a state” for rather cogent and compelling reasons.

For all the hopes pinned on Rojava or Chiapas, the state-form will continue to impact the lives of vast populations, and critical work both with and against this form—or this set of forms—is needed. “ExitStateCraft” is conceived as a forum for proposals on exit strategies from the actually existing state. The point is to keep the conversation moving forward, dialectically and haltingly, through diverging and contradictory forms—from imagining alternative states to working toward post-statist social forms, from inter- to trans- or post-national organizational structures, and from critical work with the juridical apparatus to the abrogation of the law.

Sven Lütticken, August 2021

1 Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860), trans. S. G. C. Middlemore (Vienna/New York: Phaidon/Oxford University Press, n.d.), p. 2.

2 Ernst Cassirer, The Myth of the State (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1946), p. 140.

3 Cassirer, The Myth of the State, p. 154.

4 Mahmood Mamdani, Neither Settler nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020), pp. 1–14.

5 See for instance Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “In the Shadow of the Shadow State,” S&F Online 13, no. 2 (Spring 2016), https://sfonline.barnard.edu/navigating-neoliberalism-in-the-academy-nonprofits-and-beyond/ruth-wilson-gilmore-in-the-shadow-of-the-shadow-state/0/.

6 For Extra States, see https://extracitykunsthal.org/en/exhibitions/extra-states.

7 Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space (London: Verso, 2014), p. 15.

8 Hito Steyerl, “Duty Free Art,” in Duty Free Art (London: Verso, 2017), pp. 75–99.

9 Wendy Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (New York: Zone Books, 2010/2017), p. 79.

COLOPHON

Editor: Sven Lütticken

Managing Editor: Wietske Maas

Copyediting: Aidan Wall

Proofreading: Wietske Maas and Aidan Wall

Translation (English to Dutch): Olga Leonhard

Graphic Design: LeftLoft and Sean van den Steenhoven for LeftLoft

Website Support: Babak Fakhamzadeh

Editorial Board: Maria Hlavajova, Wietske Maas, and Rachael Rakes

More in this edition

The modern nation-state is supposed to be ethnically and culturally homogenous; after World War II, both Israel’s implementation of Zionism and Arab Nationalism adopted versions of this purism—purging and excluding from the body social what refuses assimilation.

As part of FORMER WEST: Documents, Constellations, Prospects, 18–24 March 2013 at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, art critic, poet, and curator Ranjit Hoskote convened a forum on “Insurgent Cosmpolitanism” with cultural theorists and artists whose work addresses and performs the insurgent cosmopolitan condition.

Mariana Botey’s text The State Is Coagulated Blood and Bones is written as a prologue to Cooperativa Cráter Invertido’s codex-comic Sangre Coagulada y Huesos (Coagulated Blood and Bones, 2021). The two contributions have been conceived in collaboration and are to be read in parallel, allowing for a mutual disruption of discourse and image.

Long weaponized in the service of capital by the agents of neoliberalism, the nation-state is once again upheld as the bulwark of a white ethnos, securing privilege against migrants and immigrants, and against other nation-states in relations of neocolonial dependence.

From: New World Academy Reader #5: Stateless Democracy, Renée In der Maur and Jonas Staal in dialogue with Dilar Dirik, eds. (Utrecht: BAK basis voor actuele kunst, 2015), pp. 27–54

From: Once We Were Artists, Maria Hlavajova and Tom Holert, eds. (Utrecht: BAK, basis voor actuele kunst and Amsterdam: Valiz, 2017), pp. 32–52

In 1970–1971, Guyanese radical historian and anti-colonial activist Walter Rodney gave a series of lectures on the historiography of the Russian Revolution at University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Inspired by C. L. R. James’s historical work on the October Revolution, Rodney set out to reveal the parallels between the problems confronting the postcolonial regimes in Ghana and Tanzania, and those that the Bolsheviks faced in building the Soviet state.

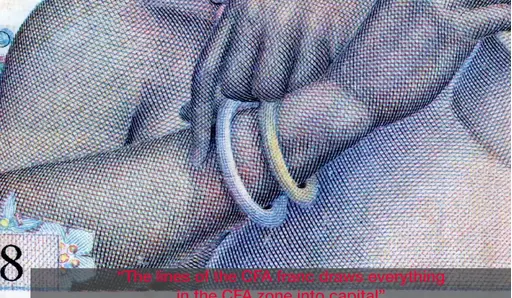

The video The Cut, The Punch, The Press (2021) is assembled from filmed fragments of a collection of 65 banknotes of the CFA franc, circulated between 1945–2021.