Author(s)

Nina Potarska

For Prospections “Standing With Ukraine. Standing With the Oppressed,” feminist, social researcher, and peace activist Nina Potarska has kindly given us permission to republish her 2016 text “Maidan and After: State of the Ukrainian Left.”

Originally published in n+1 magazine 24, New Age (Winter 2016), which gives a socioeconomic context to the Maidan uprising and describes the author’s own involvement in the protests from a feminist position, demanding direct democracy and an end to corruption and (neo)oligarchic rule; and subsequently, her involvement in helping women impacted by the war in eastern Ukraine. The republication of this text is followed by a postscript by Potarska describing her recent years of peacebuilding activist and advocacy work as Ukraine’s national coordinator for the International Women’s League for Peace and Freedom, Kyiv. Yet today—one month after the full-scale Russian invasion and its fully raging war on Ukraine—the author is faced with an acute sense of grief regarding how to carry on.

At the time, we at the center were just beginning to analyze the conditions of the agreement. We were, overall, more critical than not of the agreement’s demands for changes in Ukraine’s labor and industry protections. At the same time, we more than welcomed the Maidan protesters’ demands for an end to corruption and oligarchic rule.

That evening I went out into the square. I brought with me a poster I had made at home: I had painted the gold stars of the EU on a red background, to say that the only European union I wanted to join was a socialist one—one that offered membership on less humiliating terms than those currently being proposed to my country.

The first few days on the square, there weren’t many people, mostly just students, journalists, and activists. The activists were clear about wanting to change the government and the entire system of neo-oligarchic rule, but most of the regular people who showed up genuinely believed in joining the EU and in visa-free movement through Europe. Visa-free movement was especially attractive to people from western Ukraine who traveled to Europe to work low-wage service jobs; these jobs paid poorly by European standards, but they were better than no jobs at all. But it wasn’t just people from western Ukraine, and they weren’t only there for economic reasons. The protest was joined by students who wanted to attend university in Europe; the middle class, which had the means to travel to Europe and wanted to do so more often; and human rights activists and journalists who believed in “European values” as an expression of human rights.

There was also always a strong right-wing presence on Maidan, initially consisting of activists from the well-established Svoboda Party and eventually joined by recruits from the newly founded Right Sector and other marginal right-wing groups. My “red EU” poster was sufficiently subtle that no one bothered me about it, but when I went out onto the square with the Left Opposition, the small socialist group of which I am a member, and tried to organize discussions or give talks (for one we invited Serhiy Zhadan, a writer who had recently been attacked by anti-Maidan protesters in Kharkiv), we were quickly confronted by several young toughs who claimed we were “provocateurs” and strongly suggested we leave. The first few times this happened, we did leave. The harassment stopped for two reasons: one was that, in mid-January, people started dying. After that, there was a lot less tension between us and the right on Maidan. The other thing that happened was that the women in our group formed a self-defense battalion, just as so many others on Maidan had done. We practiced self-defense, organized lectures, and showed some movies; two of the women took part in battles with police, but as a battalion we never called for violence. Our battalion earned enough attention from the press that from then on we were more or less immune to harassment from right-wing activists. The women’s battalion was just about the only success of the left wing on Maidan; that was how we finally earned a space for ourselves there.

Our purpose at the protests was to understand the demands of the protesters and to try to formulate our own. After we’d stood up for ourselves, we managed to organize several discussions and lectures. Our leaflet “10 Demands for Social Change” was welcomed by some of the protesters—the mood on Maidan had become so radical by late January that some people felt our demands hadn’t gone far enough. In the leaflet we spoke about giving power to the people and about direct democracy, about the nationalization of major industrial enterprises, increased taxation on wealth, an end to capital flight, the need for a strict division between business and government, the right to medicine and education, and the abolition of the special security forces, like Berkut, who were at that moment systematically beating up protesters. When our activists visited the “anti-Maidan” protests in eastern Ukraine, this same leaflet, minus the demand about Berkut, was also met with understanding. (To people in the east, terrified by Russian television propaganda about the bloody nationalist coup in Kyiv, the Berkut and other police seemed like their only defense.) Support for our program confirmed the results of our Center’s research, the same ones I had sent out the morning that Maidan began: the mood of the populace all over Ukraine in 2013 was more rebellious than usual, and socioeconomic factors were the chief cause. It was these findings that allowed us not to lose our heads during the brief period of euphoria after the triumph of Maidan or succumb to the potential illusions (shared by some of our former comrades) about the utopian nature of the People’s Republics being constructed in the east under the watchful eye of Russian agents. I knew that the real nature of people’s protest was socioeconomic, and that neither of the new regimes had the interests of working people and the poor anywhere near the top of its agenda. Nevertheless, in both cases, I naively hoped for the best.

Of course my hopes were disappointed. A weakened Ukraine became yet another battlefield for two imperialisms. Under cover of protecting their fellow Russians or defending Ukraine’s territorial integrity, Russia and the West both encouraged a slow-moving but violent conflict. Throughout 2014, the left opposition struggled to formulate our demands and our position. It was a terrible, terrifying year for many, and we were no exception. Yesterday’s activists from the same side of the barricades went off to fight on different sides of the war. Some of them were captured and some were killed. Others wore themselves out trying to help the Ukrainian army: they collected money, transported armored vests and artillery. Meanwhile just a few small groups kept trying to agree on a united antiwar text. For my part, I decided I would not help anyone who had taken up arms; I would only help civilians fleeing the war with whatever I had: my apartment, my clothes, and the clothes of my children.

For almost a year I hosted families fleeing the fighting in eastern Ukraine; they were the ones who helped me understand the extent to which the war had been foisted on ordinary people by ceaseless propaganda from both sides and then presented as the natural order of things. Most people still couldn’t understand how it had happened, how some serious but not intractable disagreements had led to “all this.” Then, in late winter 2015, after the European-brokered cease-fire at Minsk had significantly decreased the intensity of the fighting, I traveled to the east to talk with the women who lived there. I believe women bear the brunt of any war, whether as civilians suffering bombardment, or as wives or mothers of soldiers dying at the front, or as those tasked with providing food and warmth under impossible circumstances.

In the east, women who had spent the past six months in and out of basements, watching their sons and brothers and husbands go off to the front, were now returning to “normal” life. In the rebel-held territories, this meant long lines for humanitarian aid from the oligarch Rinat Akhmetov and long days searching for affordable food in the grocery stores. In January the Ukrainian government had imposed a de facto embargo on the importation of goods and services into the occupied territories. Clearly intended as a harsh lesson to the people who lived under rebel rule, its net effect was to anger the residents and force them into the arms of Russia. Food and other goods that had, somehow or other, continued to make it to the territories from the rest of Ukraine now slowed to a trickle; they were partly replaced by Russian goods, but since these, too, had to cross a border and be subject to both official and unofficial tariffs, they were not exactly plentiful. The result was that food was becoming scarce.

Municipal services were also scarce. The government had “melted away” and only partly been replaced by a new one. In Donetsk, buildings damaged in the fighting of the past year remained mostly unrepaired, and the streets of this once uniquely clean (for Ukraine) city were littered with garbage. Too many people had left, and the government that remained was too busy fighting its war.

For ordinary residents, concerns were more mundane. In order to receive pensions and other government payments—an important source of livelihood for much of the population, especially the vulnerable population that had not had the resources to leave the territories where fighting was taking place—they had to travel into unoccupied Ukraine. Before the embargo, this had been simple enough. After it was imposed, people were often left standing in checkpoint lines for twelve hours or more.

I hope it doesn’t strike anyone as pro-government propaganda if I say that in the government-controlled territories life was significantly better. There was food in the stores, and currency in the ATMs, and the men with guns were, on the whole, much less likely to detain you for no apparent reason. On my last visit to Donetsk I was detained and questioned for several hours by their MGB, or secret police. I was released, and plan to go back again, but it’s hard to escape the feeling of paranoia that the rebel government labors under. In Ukrainian-controlled territory, things are more relaxed. And yet there, too, people have found themselves in a war zone, mostly against their will.

In the sociological questionnaire I distributed, I asked people who they thought was fighting whom, and what the demands of the warring sides were, as far as they understood. My respondents had various views, but more often than anything they expressed their surprise that people had taken up arms against one another; they spoke of the fact that simple people had no reason to fight, that it was the oligarchs and politicians who were fighting one another. People like them, they believed, had no influence on or say in the situation.

Russia no longer denies that it was responsible for seizing Crimea, nor does it deny that it has propped up the People’s Republics, but the situation inside Ukraine remains complicated even though wartime is unfriendly to ambiguities. Even after the last Russian “volunteer” rides the last Russian tank off Ukrainian territory, the problems that allowed the regions of Ukraine to fight one another will persist. The policies of the current government toward the war’s displaced persons, which make it extremely difficult for them to set up new lives in unoccupied Ukraine, are cruel and inhumane: the government is in effect trying to blame them for the war. Instead of supporting them materially and psychologically, it gives them populist slogans like “The East Is Ukraine,”and “Crimea Is Ukraine.” It takes away their right to vote, degrades them at checkpoints between occupied and non-occupied Ukraine, forces old men and women with children to stand in lines for days. The people who suffer the most from this war are the poor; those with means left the conflict zone long ago.

There is no good or bad side of this war to me. Amid the geopolitical wrangling over an area where the interests of Russia and the United States collide, it has been forgotten that Ukraine is also a 45 five million people, one quarter of whom live on less than $4 a day.

The situation that we experienced eight years ago was a localized version of today’s nightmare, which has swept the entire country and affected everyone. From my interviews in 2014 and 2015, residents of the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic (Donetskaya Narodnaya Respublika, DNR) and Luhansk People’s Republic (Luganskaya Narodnaya Respublika, LNR) often said that it would only be when Kyiv itself is shelled that residents of the capital would understand the cruelty of their accusations against and stigmatization of the refugees and those who decided to stay in their homes. But now we are only formulating new accusations, trying to find the causes of our pain and frustration; we do not have enough time to fathom the reports of friends and relatives dying and the destruction of the cities in which we lived our former lives.

Since the Maidan, I have been researching the situation as it relates to war. My first work on the life of women in war conditions was “The War and the Transformation of the Everyday Life: The Female Perspective.” In this text, the interviews were collected from people on both sides of the demarcation line between Kyiv- and non-Kyiv governed areas. We begin this text like this: “In a situation where the conflict reaches the level of armed confrontation, it is very difficult to stop and start talking. It’s even harder to start listening.” 1 We listened to ordinary women whose everyday lives had radically changed since the beginning of the military conflict. How had their daily worries and fears, on both sides of the dividing line, changed in this new society? What structural problems had been introduced into their daily lives? Who did they rely on and who did they blame in critical situations? What survival strategies did they choose? Who could stop the confrontation and how, in their opinion? And what conclusions could be drawn from this about the society in which we live and the society without war in which we want to live? In a situation of armed conflict it is important to hear how people’s daily lives have changed in order to understand at what points—of everyday life and its socioeconomic structures—is the situation deteriorating. Because when the conflict is over, the socioeconomic structures will either remain the same or deteriorate further if adequate measures are not taken. We wanted to overcome the stigma in which refugee women lived—women who decided not to leave the occupied territories. We wanted to contact those who wanted to continue looking for a solution to this war together, those who wanted to restore the kinds of human connection that can prevent the dehumanizing divide between “us” (people) and “them” (the enemy) from forming.

Since 2016 I have been working as Ukraine’s national coordinator for the International Women’s League for Peace and Freedom, Geneva. The objectives of the program are to improve the organization of, to facilitate the participation of women in, and to ensure that gender perspectives and responses are made mainstream within national and international structures. The focus is on identifying human rights violations based on gender analysis, researching government responses to these issues, and finding ways to approach transitional justice and developing strategies for their implementation. Part of my activities are monitoring the needs and observing the rights of women living near the contact line in relation to gender-based violence as well as conflict-related violence; enacting gender-inclusive mediation of conflicts; and preparing reports on the observance of women’s rights in the UN system.

My position in this organization has allowed me to deepen contacts with women from grassroots organizations, bring their voices to the highest levels of the UN, and to facilitate their participation in discussions with our government outside of Ukraine. Over the years, our partner organizations have been well trained in nonviolent and dialogue methods—they know how to advocate for the problems of various vulnerable groups at the local, national, and international level. We have united into an informal network of women activists working at different levels. In our statement, we say the following about ourselves:

We, active women, have united regardless of our language, territory, sexual orientation and gender identity, health, psychological state and different forms of disability, family and material state, absence or presence of children, age, ethnicity, political, religious or other convictions, to create a network in order to advance opportunities and foundations of peace building and inclusive civic dialogue in Ukraine. We look at the process of peacebuilding in the context of ongoing conflict as creation of institutional and cultural conditions for consideration of basic needs of different groups of society, creation of a common space for participation in decision-making and just distribution of resources and goods.

We focus on defending interests of different groups of women to increase inclusivity and legitimacy of peace negotiations among the majority of population to guarantee sustainability of these processes through advocacy and political participation. Our approach is based on analysis of power relations, gender equality and human rights. Participants of the network operate based on principles of: openness, nonviolence, trust, participation, respect for diversity and support. 2

In addition to other forms of invisible work, which we have tried to avoid doing publicly, we have held two symbolic meetings as “Women’s Dialogue without Borders.” Daily, thousands of people cross the checkpoints in the area of the Joint Forces Operation zone, putting their life and health at huge risk; they simply have no other choice. Women’s initiatives on both sides of the demarcation line stand to protect the basic rights of citizens for life and security. On 2 October 2019, International Day of Non-Violence, representatives of a women’s initiative conducted the action “Women’s Dialogue without Borders” on both sides of the demarcation line. With this action they sought to address all conflict parties, who were requesting that they ensure security and right for life for those forced to live in constant danger.

On the International Day of Non-Violence we, women from different parts of Ukraine, met in the areas between each side to declare our commitment to nonviolence, and to promote a culture of peace and understanding. We wanted to hear each other, and we wanted to be heard. For five years we had been living and working in a region of armed conflict in Donbas. Every day we had heard the needs of people, we had seen the realities of the war in which people lived, and we understood that regardless of territorial affiliation, political situation, or other factors, the basic needs of people on both sides of the contact line were the same: security, connection, and humanity. From this understanding we formulated demands, which we voiced on behalf of ourselves and the communities which we had been working with on both sides of the contact line, they included: increasing the number of crossing points to and from the territories temporarily uncontrolled by the Government of Ukraine; ensuring safe waiting areas and access to humanitarian services and toilets with tables for diaper change; ensuring access to running water, drinking water, a place to warm-up, and shelter in cases of fire; setting up government-funded first aid centers at all crossing points; renewing direct railway and bus connections between the controlled and temporarily uncontrolled territories of Ukraine; a ceasefire from both sides with the aim of ensuring security for civilian citizens; transitioning to peaceful conflict resolution by means of negotiations and the inclusion of representatives (of all genders) of civil society organizations—peace and human rights organizations and women’s organizations—on all levels in these negotiations; and guaranteeing security for all participants of dialogue processes on both sides of the conflict.

On 24 May 2021, the International Day of Women for Peace and Disarmament, we organised another “Women’s Dialogue without Borders” action to discuss the problems faced by the citizens of Ukraine in the occupied territories of Ukraine (Okremi raiony Donetskoi ta Luhanskoi oblastei ORDLO). “For seven years we have been separated by checkpoints from our relatives and friends, but over the years we have become accustomed to the new rules. It is bitter when, having the same passports, we do not have the same rights and recognition from our state as full-fledged citizens. On the other hand, because of the closed checkpoints, we cannot leave our cities to meet with our families and friends,” one activist said. 3 We again formulated and developed demands together based on these meetings.

Since the beginning of the war in 2014, my work and research has been connected with the study of themes of community and the moods of its people, and has attempted to find points for building peace through an inclusive dialogue. Through deep reflection, we—women who have been engaged in these dialogues—have come a long way toward building new meanings and searching for new ways to glue this society together. But now I have no ideas for continuing this work—the necklace that we strung bead by bead fell apart again, and so far I don’t even have the strength to look for its scattered parts. We do not even know who will be able to survive tomorrow, so we just check in the mornings and the evenings who is still alive.

2 See the manifesto “Women’s Network for dialogue and inclusive peace,” 21 September 2019, www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=119975459393854&id=119133036144763.

3 Video documentation from these meetings was featured on DOM TV and is available online in Ukrainian from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uQTGJ3ujOgE.

More in this edition

For Prospections “Standing With Ukraine. Standing With the Oppressed,” feminist, social researcher, and peace activist Nina Potarska has kindly given us permission to republish her 2016 text “Maidan and After: State of the Ukrainian Left.”

Oleksiy Radynski writes on the fifth day of war from a suburb of Kyiv for a case against the Russian Federation.

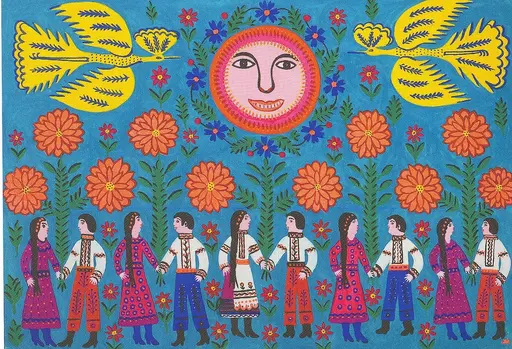

It is the thirteenth day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Researcher and art historian Asia Bazdyrieva remains in Ukraine, south of Kyiv with her family. She has shared a diary entry on Instagram for every day of the war so far. Here is her entry for Tuesday 8 March 2022—also International Women’s Day—republished above as images, and below as text-transcript with kind permission of the author.

What follows is a makeshift reading (and listening) list of what we believe are relevant articles and interviews that give historic context on the invasion of Ukraine and how we at BAK—and a broader international left opposing this and all wars—can express solidarity and exert political pressure right now.

We at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, condemn the brutal military invasion of Ukraine, launched by Vladimir Putin.

Within the long-term research itinerary Propositions for Non-Fascist Living (2017–2021), BAK asked artists, philosophers, scholars, and activists from multiple (political) geographies facing contemporary fascisms how they engage with the question of what constitutes non-fascist living.