until

48-hour Selma

An online screening of Tony Cokes’s Evil.27: Selma (2011)

For 48 hours, from Thursday 11 June 2020, 18 hrs CET to Saturday 13 June 2020, 18 hrs CET BAK’s online forum, Prospections, presents a screening of Evil.27: Selma (2011), artist Tony Cokes’s audiovisual meditation on protest and imagination against the realm of mass-image circulation and anti-black oppression in the United States.

Presented as a part of Prospections’s ongoing focus, Tactical Solidarities, Cokes’s work considers the effect that instant mediation and transmission has on people’s capacities to organize in new and trenchant ways—a perennial question under particular pressure in this critical moment of rage, demonstration, and change.

The work was on view at BAK very briefly earlier this year as part of an exhibition and public program with and around the work of Tony Cokes. Cut short due to the outbreak of Covid-19, it will reopen at BAK on 16 October 2020, to run through 10 January 2021.

From the exhibition guide of Tony Cokes: To Live as Equals

Evil.27: Selma (2011 9:00 MIN.)

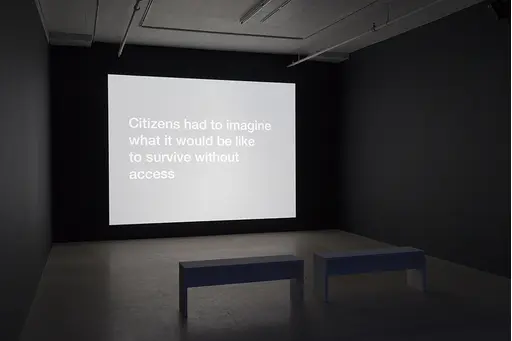

“The American Civil Rights Movement took hold in a society moving from radio to television,” reads a slide from Evil.27: Selma, borrowing its core text from “Notes from Selma: On Non-Visibility” by the Alabama collective Our Literal Speed. The text is based on emblematic events of the Civil Rights era, such as the marches from Selma to Montgomery, the arrest of Rosa Parks, and the Montgomery bus boycott. Mixing this text with lyrics and soundtracking by singer and songwriter Morrissey, “The more you ignore me, the closer I get,” the work reconsiders the contemporary dominance of the image as evidence and record. By invoking a period of civil mobilization in the United States that came about in a time without mass image circulation, the video examines what is lost when “everything is instantly visible.” In redeploying modes of information dissemination, the work examines the weight of visibility as it is organized in the media to govern what is perceived as reality.

It is worth noting that Cokes’s 2019 work, The Morrissey Problem, indirectly revisits Evil.27: Selma by discussing the singer’s recent devolution into right-wing ideology, retroactively applying a critique and rereading of the lyrics and soundtracks employed in Cokes’s works. The video adapts in full a 2019 essay from The Guardian by journalist Joshua Surtees, in which the author recounts how, as a British-Jamaican longtime fan, he watched with increasing horror the descendent steps of Morrissey’s fall into fascism. Speaking in the form of a break-up letter to the singer, Surtees calls him “the pop version of Nigel Farage—the kind of person your younger self would have despised.” His words ring true to a great many of Morrissey’s disenchanted fans, Cokes among them.

“The American Civil Rights Movement took hold in a society moving from radio to television,” reads a slide from Evil.27: Selma, borrowing its core text from “Notes from Selma: On Non-Visibility” by the Alabama collective Our Literal Speed. The text is based on emblematic events of the Civil Rights era, such as the marches from Selma to Montgomery, the arrest of Rosa Parks, and the Montgomery bus boycott. Mixing this text with lyrics and soundtracking by singer and songwriter Morrissey, “The more you ignore me, the closer I get,” the work reconsiders the contemporary dominance of the image as evidence and record. By invoking a period of civil mobilization in the United States that came about in a time without mass image circulation, the video examines what is lost when “everything is instantly visible.” In redeploying modes of information dissemination, the work examines the weight of visibility as it is organized in the media to govern what is perceived as reality.

It is worth noting that Cokes’s 2019 work, The Morrissey Problem, indirectly revisits Evil.27: Selma by discussing the singer’s recent devolution into right-wing ideology, retroactively applying a critique and rereading of the lyrics and soundtracks employed in Cokes’s works. The video adapts in full a 2019 essay from The Guardian by journalist Joshua Surtees, in which the author recounts how, as a British-Jamaican longtime fan, he watched with increasing horror the descendent steps of Morrissey’s fall into fascism. Speaking in the form of a break-up letter to the singer, Surtees calls him “the pop version of Nigel Farage—the kind of person your younger self would have despised.” His words ring true to a great many of Morrissey’s disenchanted fans, Cokes among them.

with: Tony Cokes